At UC Santa Barbara, student activism has long held a prominent place in campus life and the surrounding Isla Vista community. For decades, students have mobilized to raise awareness and demand action on political, social and environmental issues at the local, state and international level.

North Hall Takeover

On Oct. 14, 1968 at around 6:30 a.m., 12 Black students took over North Hall and locked themselves in the building for the next 10 hours until the administration listened to their demands for structural change and inclusivity.

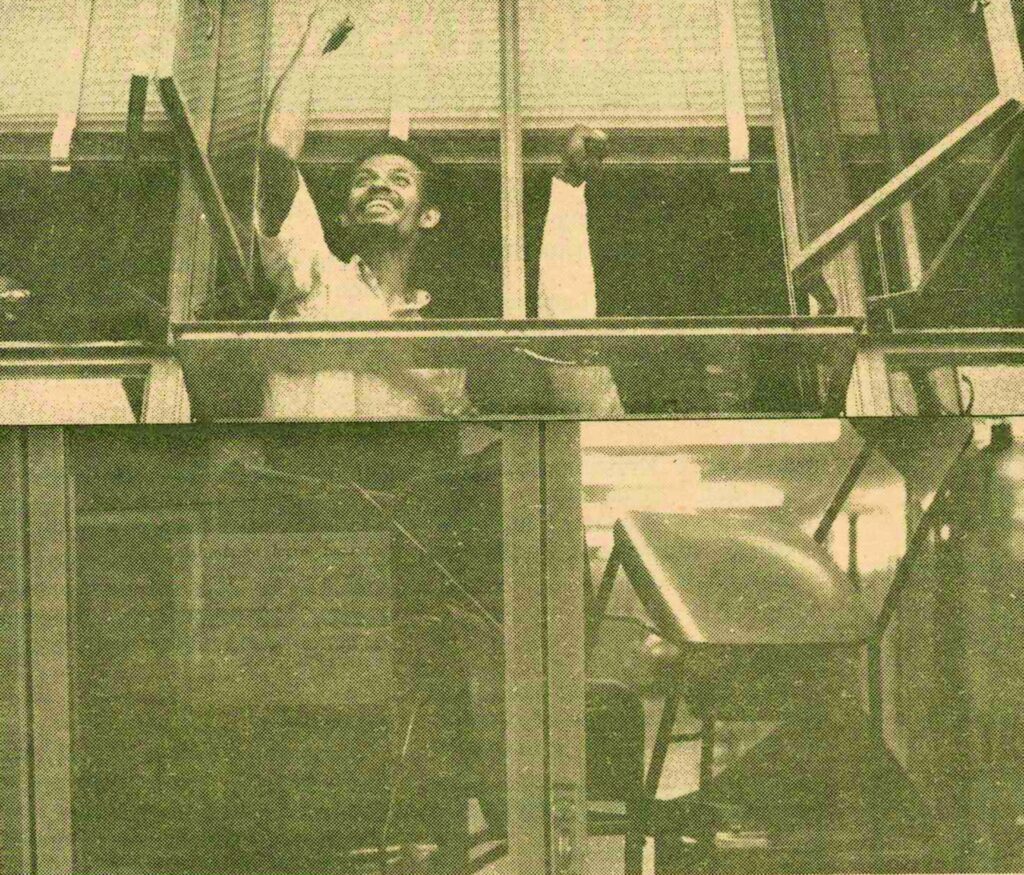

While they occupied the building, the students drew a crowd of around 1,000 people. Daily Nexus Archives

This day of protest demanded material change for UCSB’s Black student population and forever changed the school’s curriculum.

That morning, the group gave their list of eight demands to then-Chancellor Vernon Cheadle, which included the development of a college of Black studies and the prohibition of any race-based student harassment.

In the hours they occupied the building, the students drew a crowd of around 1,000 students and staff. One student in particular, Booker Banks, played a key role in engaging with and educating the audience about their demands through the second-floor window with a microphone.

The group of 12 strategically decided to take over North Hall because it held the mainframe computer that the University could not run without.

The students hung a banner that read “Malcolm X Hall,” temporarily renaming the building in commemoration of the work of Malcolm X, a founding leader of the Black Power movement of the 1960s.

In the late afternoon, the chancellor’s office notified students that they had agreed to all but one of their demands, the firing of Athletic Director Jack Curtice and head of the physical activities department Arthur Gallon for their alleged racist behavior.

While not officially renamed, after that day, North Hall would be forever remembered as Malcolm X Hall, and a year later, the University established a Black studies department. This paved the way for the establishment of the Chicana and Chicano studies department, the Asian American studies department and the feminist studies department.

In 2012, the Black Student Union sent a list of demands to Chancellor Henry T. Yang, one of which was to create a North Hall display to commemorate the events and legacy of the takeover. The display now lines the outside of the building with pictures of that day, showcasing the student activists whose work made the takeover possible.

In 2012, the Black Student Union created a North Hall display that lined the outside of the building with pictures to commemorate the legacy of the takeover. Amy Dixon / Daily Nexus

Bank of America Burning

On the afternoon of Feb. 25, 1970, William Kunstler, an attorney and civil rights activist known for defending the high-profile case of the Chicago Seven, spoke at Harder Stadium. Kunstler addressed instances of violence between students and law enforcement in I.V. as well as other contentious local issues.

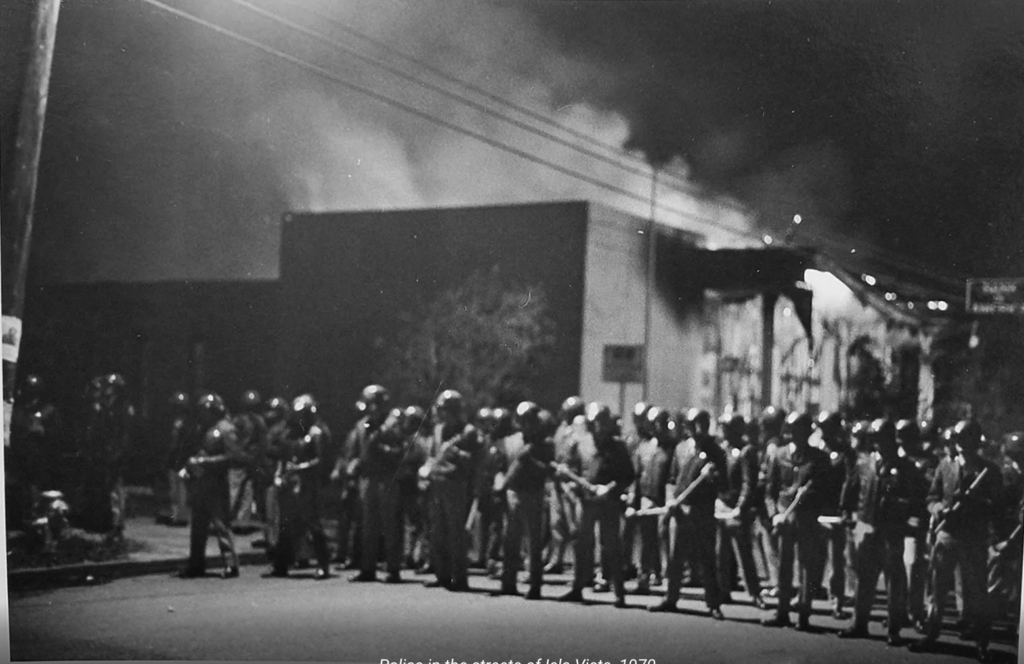

Policemen stationed in Isla Vista. Courtesy of KCSB

“I have never thought that breaking of windows and sporadic, picayune violence is a good tactic,” Kunstler said in his speech. “But, on the other hand, I cannot bring myself to become bitter and condemn young people who engage in it.”

After Kunstler’s talk concluded, attendees walked together to attend a rally at Perfect Park in I.V., which was then patrolled regularly by police officers. Officers stopped and tried to arrest Rich Underwood, a former UCSB student, after mistaking an open bottle of wine in his hand for a Molotov cocktail.

When Underwood resisted arrest, officers beat him. Additional officers in riot gear arrived on scene, and a group of around 500-700 students clamored on the street, with some throwing rocks and bottles at the police vehicles.

The agitation of students spread as they moved through I.V., breaking the windows of real estate agencies and setting several police cars on fire. Then, individuals on the streets set the I.V. Bank of America building — located at present-day Embarcadero Hall — on fire.

Tim Owens, a third-year student at UCSB during this time, worked as a programmer for campus radio station KCSB-FM. Owens witnessed the burning of the bank from across the street and later created a radio documentary about the events, called “Inside IV: There Where the Bank Burned.”

Owens said the incident began when a group of people began to push a dumpster through the bank doors, causing the curtains on the interior of the bank to ignite. The flames spread, and soon the entire building was on fire.

“I don’t know if the fire trucks came and went, but they didn’t stay if they came,”

Owens said in an interview with the Nexus. “We just stood around and watched the bank burning and thought ‘Oh, oh, this is not good.’”

Owens left and returned to the scene the next morning — the entire building had “burned to the ground,” leaving only an “emaciated vault.”

According to Owens, the bank was specifically targeted due to its location and students seeing it as a “symbol of the establishment.”

During this time period, many students at college campuses across the country opposed the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, holding protests and rallies. According to Owens, student activists at UCSB were part of this new wave of younger people who questioned and opposed “the establishment” and believed in promoting peace.

Student and editor of El Gaucho, a campus publication which was active during the time period, Becca Wilson said of the bank: “It was the biggest capitalist thing around. It was a symbol of the corporations that benefited from war and were oppressing people all over the world.”

In the aftermath of the events, then-California Governor Ronald Reagan declared a state of emergency and called in the National Guard. Police arrested around 300 people for their involvement in the incident. Ultimately, a jury convicted four individuals, with two charges of arson and four misdemeanors adjudicated.

LGBTQIA+ Student Organizations

In 1970, students at UCSB established the Gay Student Union. Over the years, the name had several iterations, including the Gay People’s Union and the Gay Lesbian Student Union. Six years after the union’s formation, students formed the UCSB Coalition Against Homophobia.

Student groups often tackled national issues, including blood banks discriminating against gay men and the legalization of same-sex marriage. In 1998, the Queer Student Union (QSU), Associated Students (A.S.) Statewide Affairs Organizing Director Sergio Morales and Student Advocate Rodney Clara organized a protest of blood drives at UCSB. The group argued that the Food and Drug Administration policy that barred men who had sex with other men from donating blood violated the UC’s anti-discrimination policy.

“The reason we’re here is that this is a systematic discrimination against a large constituency on campus. It’s assuming that all queer men are HIV positive,” Morales told the Nexus at the time.

1994 Hunger Strike

Student activists’ efforts led to the establishment of UCSB’s Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies in the fall of 1970, making it the first department of its kind in the UC system. At this time, it employed six faculty members, each of whom was a “half-timer” — employed 50% in the Chicana/o studies department, and 50% in another academic department — making it a department of only three full-time faculty members.

Students participating in the hunger strike met with other students outside of Campbell Hall. Courtesy of The Current

By 1994, UCSB’s Chicana/o studies department still consisted of three full-time faculty members, leading a group of nine student activists to take action. They planned a hunger strike, which organizers held from April 27 to May 5, 1994.

Professor Ralph Armbruster-Sandoval, who joined the Chicana/o studies department in 1998 and has published a book on Latine student hunger strikes in California, described the students’ mindsets in an interview with the Nexus.

“Some people viewed [the department] as a tokenized thing,” Armbruster-Sandoval said. “University administration gave it to the community to kind of shut us up. ‘We gave you guys a department, what more do you guys want?’ That kind of thing, and they were like ‘Well, we want a real department.’”

The student activists wanted the department to be more engaged in issues affecting Santa Barbara’s Latine community, including mistreatment and deportation.

“If you’re a Chicano studies professor and your position came through organizing and resistance, then you should keep doing that,” Armbruster-Sandoval said of the activists’ beliefs on the matter.

The student activists started as a group of nine, and a few days before they made their strike “official,” they held a meeting at El Centro, where student-led cultural and advocacy organization El Congreso meets. At the meeting, the activists announced their plan to hundreds of people.

“It became like a big community event of a couple of hundred people,” Armbruster-Sandoval said. “It went from a small group of people — about 10 — to much bigger, like a machine almost.”

The students who joined the original activists did not all participate in the hunger strike, but assisted them in different ways, including hosting nightly rallies outside of Cheadle Hall and Campbell Hall. Some also acted as their security, preventing individuals who opposed the activists from harassing them.

The activists had a large number of demands for the university administration, which they selected after congregating and deciding which issues to prioritize. The activists’ demands included expanding the Chicana/o studies department from three faculty members to 15, as well as a doctoral program, a community center, the preservation of the Educational Opportunity Program and greater diversity on campus.

Progress was made after some of the activists’ parents visited UCSB and demanded that university administration listen to their demands. Then, the activists selected three negotiators who were not participating in the hunger strike to represent them.

The activists’ efforts paid off on May 5, with university administrators agreeing to increase the number of faculty in the Chicana/o studies department by 1997, proposing a doctoral program, funding a community center in I.V. and increasing recruitment of Latine students.

Armbruster-Sandoval describes the activists’ actions and impact as beyond tangible — their efforts pushed for the Latine community at UCSB to be treated as “dignified human beings.”

“How do you achieve dignity really in a system that’s always treated, especially Mexicans and Latinos, in an undignified way?” Armbruster-Sandoval said. “They tried to make it concrete by issuing demands and in granting those demands, they could kind of hold their heads up a little bit higher, and say, ‘I belong here.’”

Queer Weddings

From the 1990s until the mid-2010s, when the U.S. legalized same sex marriage, student groups hosted queer weddings during UCSB’s Pride Week. Then-Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Michael Young unified couples in a group marriage ceremony at Storke Plaza.

“Marriage is not the end-all, be-all,” QSU Co-chair Tanya Paperny said during the ceremony in 2006. “[This wedding] represents the culmination of years of struggle to have queer relationships recognized.”

The wedding ceremony in 2013 served as the final event of the year’s Pride Week. Courtesy of Associated Students Gallery

2020 activism

Right before the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, graduate students protested and later struck in solidarity with the UC Santa Cruz grad workers as part of the Cost of Living Adjustment movement.

In March 2020, the University made all spring quarter instruction remote. According to Nexus coverage at the time, the extended break from usual activities gave students time to reflect, build community relations and advocate for changes they hoped to see across the UC. Student-led organizations such as the Cops Off Campus Coalition and the Asian Coalition held remote and in-person meetings to discuss issues that students of color were facing.

“I think that this past year brought to the forefront and brought to the attention of a lot of folks the reality that many of us have been living for quite a while,” UC Student Regent and UCSB graduate student Jamaal Muwwakkil told the Nexus at the time.

Students, faculty and community members marched to Sands Beach in 2020 in light of police brutality against Black communities. The murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade and others sparked a national movement that made its way to UCSB in late May.

Community members gathered at Sands Beach. Nexus File Photo

Then-student Michael Sanders organized the march of close to 1,000 people. He recently told the Nexus he was motivated to take action because “it just seemed like nothing was being done in Isla Vista.”

“It just seemed like nobody was doing anything. So I just took it upon myself,” Sanders said. “I never thought it was gonna be as big as it was. I just wanted a small group of students to get together and air their grievances and [have] a safe, open space, and then it turned into something bigger.”

Sanders said that while he believes mobilizations are important, the experience inspired him to delve into direct action. After graduating in 2020, Sanders helped found Feed The Block, a mutual aid collective. Sanders encouraged students to remember “there’s a world outside of the University and organizing is bigger than being a student.”

“I just hope that fellow students don’t feel discouraged by the current administration that’s in power, or the current political climate around being an organizer,” Sanders said. “This administration is temporary, but organizing and your values are forever.”

In terms of activism related to the pandemic, UCSB’s chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA) advocated for $900 relief checks for students. In May 2021, YDSA members marched to Yang’s house, demanding that the university redistribute federal money directly to students. The campaign was ultimately unsuccessful. However, YDSA leadership said they remained hopeful for the upcoming in-person academic year.

“I’m sick and tired of the University telling us ‘no’ while they line their pockets, letting their buildings remain vacant while people sleep outside in the street, charging full rent during a pandemic and charging full tuition,” YDSA volunteer Gina Sawaya said during the march.

UCSB Stop Sable

UCSB’s long history of environmental activism stretches all the way back to Jan. 28, 1969, when the Santa Barbara area experienced one of the largest oil spills in the United States at the time. Equipment in an oil rig owned by Union Oil had become faulty, causing 1,000 gallons of oil to spill per hour. This spill was devastating to the Santa Barbara area, causing the normally bright blue ocean to become completely black, with many of the sea’s inhabitants having to suffer the consequences.

Members of UCSB Stop Sable rallied against the pipeline earlier this year. Anusha Singh / Daily Nexus

Just a few weeks after the spill, 21 UCSB faculty members formed a group called “The Friends of the Human Habitat” to create a more professional form of environmental education at UCSB. By the fall of 1970, the university had established its environmental studies (ES) program, becoming one of the first colleges to offer such a program.

Since then, UCSB has become known for its robust ES program, where students and faculty both work toward environmental education.

One of the most prominent environmental activist groups in recent years is UCSB Stop Sable, a campaign led by the A.S. Environmental Affairs Board (EAB), California Public Interest Research Group (CALPIRG) and the Environmental Law Club at UCSB. Students formed this relatively new coalition in October of last year to unite similar organizations across UCSB as a response to Sable Offshore’s efforts to reopen the Refugio Pipeline after another massive oil spill in 2015.

According to fourth-year environmental studies and communication double major Jenna McGovern, who is also an EAB co-chair and Stop Sable co-founder, the coalition aimed to be a more organized opposition by allowing students to come together to amplify the impact of their activism.

“We just try to create a space where all these groups can come together and share the different goals that everybody has going on … just all of these environmental groups, and there isn’t really a great way for all of us to connect,” McGovern said.

McGovern explained that the coalition emerged to unify environmental activists, making their sentiments more accessible.

“So in the fall was when there was a big hearing going on at the [City of] Santa Barbara Planning Commission for Sable … and just all of the attempts to try and get this system restarted has been happening since, like, I think 2023 or 2022 is when they kind of started moving it over,” McGovern said.

Since the coalition’s formation, they have rallied hundreds of students to attend hearings in opposition to the pipeline. In February of this year, hundreds of students attended a hearing that deadlocked the transfer of county permits for the Las Flores Pipeline System from ExxonMobil to Sable Offshore.

“At that [hearing] in particular, that was like our magnum opus. There were so many people there, like hundreds and hundreds of students; it was so cool,” McGovern said. So we just had this mass force of students and community members that were trying to get involved and just be there and show support.”

McGovern also spoke about the impact Stop Sable has had beyond UCSB, attributing their Instagram account @ucsbstopsable to such a widespread reach.

“I think we have over 650 followers now, which has been really great. And you know, we can see the metrics of it, and it has reached like, over 15,000 people, which was just so mind-boggling,” McGovern said. “We get [direct messages] from people in the community, just like general Santa Barbara and who are interested in this. We’ve also had contact with people in [San Luis Obispo] and all these other UCs and stuff like that have been like, ‘I see the work that you’re doing,’ and that’s been so cool.”

Munger Hall

Frequently referred to as “Dormzilla,” Munger Hall was a proposed dormitory that was in development for over a decade. Charles Munger designed the building and was going to contribute hundreds of millions of dollars to help fund the project. When the University initially announced the project in 2021, the project was consolidated to a single 11-story structure, with nine floors housing 4,536 individual student bedrooms, most of which had no windows.

In a project hearing, planners announced that the residence hall arrangement would contain eight students who each had individual bedrooms and would share a suite that branched into an eight-suite hall, where they would all share a large kitchen area and lounge room. A residential advisor would’ve been responsible for 62 students per area, over twice the number of students compared to other UCSB residence halls. The pattern repeated eight times per floor, with each floor holding 504 students.

This ambitious residence hall quickly garnered backlash. Community members made two petitions in an attempt to halt the project and totaling over 18,000 signatures cumulatively. Architectural consultant Dennis McFadden, who had worked as an architect for UCSB for nearly 15 years, resigned in protest of the project on Oct. 24, 2021, which caused the story to gain national coverage from outlets such as CNN and the New York Times.

A week after McFadden’s resignation, hundreds of students assembled at the front of the UCSB Library in protest of the project, with students holding signs and reciting speeches. This protest also fell under Parents’ Weekend, with protestors chanting “Don’t send your kids here” as they marched through campus.

Following the mass criticism, Chancellor Yang created a review panel led by the Academic Senate to take public input for recommendations. The panel suggested various changes to the project, with UCSB eventually scrapping the project entirely in 2023.

Pro-Palestine encampments

On May 1, 2024, the UCSB Liberated Zone, an autonomous pro-Palestine collective, set up encampments on the lawn between the library and North Hall, also known as Malcolm X Hall, in a show of “solidarity with Palestine, Sudan, Haiti, Congo, Tigray and all oppressed peoples.”

The encampment would go on for 54 days, becoming the longest remaining UC encampment. Lizzy Rager / Daily Nexus

Israel established itself as a sovereign state in May 1948. It is estimated that 750,000 to 1 million Palestinians were displaced from their homes from 1947 to 1949, also known as al-Nakba, or the Catastrophe. Decades of conflict ensued between Israel and Palestine under the occupation.

On Oct. 7, 2023, Palestinian militant group Hamas attacked Israel, with estimated casualties of 1,200. Since then, Israel has killed an estimated 62,614 Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank as of Aug. 25, 2025, from bombing, gunfire and starvation from an aid blockade.

In a letter addressed to Yang and UCSB administrators on May 3, 2024, the Liberated Zone stated that “UCSB’s involvement in Palestinian genocide, through academic, economic, and carceral collaboration, has become unbearable.” They went on to list out their seven demands for the University.

The Liberated Zone’s first demand was the disclosure of any investments and partnerships with the three largest U.S. weapons manufacturers, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman and Lockheed Martin, who have all given funding to UCSB. The Israel Defence Forces uses weapons and technology from these manufacturers.

The second demand was divestment from all weapons manufacturers, as well as BlackRock and Vanguard, the top shareholders for those manufacturers. They called for divestment from unethical materials such as cobalt used in the UCSB materials department’s laboratories, which is often mined using exploitative child labor, primarily in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Lastly, they demanded divestment from “colonial infrastructure” such at the Thirty Meter Telescope and research on Mauna Kea, which is sacred land in Hawaiian culture.

The group also called on UCSB to demilitarize research by breaking relationships with weapons manufacturers and abolishing UCSB’s police department. They demanded for an academic boycott of Israel, increased protection for pro-Palestine and anti-war speech and a public acknowledgement of “the atrocities committed against the people of Gaza” and for UCSB to call for a permanent ceasefire and end to occupation in Gaza. Finally, the Liberated Zone demanded that UCSB reinvest these resources into the campus through the implementation of a Palestine studies program, immediate financial subsidies for Palestinian students and the development of student housing.

The encampment would go on for 54 days, becoming the longest remaining UC encampment. As the weeks progressed, the group set up dozens of tents on the lawn while hosting several events such as food giveaways, de-escalation and EMT training, vigils and poetry readings.

On June 23, 2024, over 75 police officers disbanded the encampment, arresting five students, with the University meeting none of their demands.

Later last year, on Sept. 24, 2024, the UC Police Department (UCPD) issued a search warrant for the Instagram account of the UCSB Liberated Zone, with a court date set on Nov. 22, 2024.

On Dec. 20, 2024, Judge Pauline Maxwell denied the search warrant request, saying it was too broad.

Girvetz Hall Takeover

On June 10, 2024, a separate group of pro-Palestine protesters called Say Genocide UCSB occupied Girvetz Hall with the demand that UCSB “release a statement recognizing the genocide in Palestine.” The protestors covered the classrooms with fake blood, fake bodies and signage.

The night of June 11, 2024, a community member close to university administration warned the protestors of oncoming police. Around 1 a.m. on June 12, 2024, the university sent an emergency message to students regarding a large-scale police operation. Subsequently, hundreds of students gathered with the protesters around Girvetz Hall. An hour later, over 40 officers from the UCPD and the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office surrounded the protest in riot gear. The building was vacated upon arrival, and no one was arrested.

Conclusion

These different acts of protest have helped shape campus culture, academic programs and the surrounding community. Through decades and generations, UCSB students have organized around issues they believe in and demanded that their educational experience be inclusive to the diverse student population.

As proud democrats, we must stand up to the FoxNews-watching republitard forces that our constantly attacking are education system. We no that it takes a village and thankfully we’ve got one! We are democrats….we are against are corrupt police and milatary, we our smart enough to now that the rich don’t pay there fare shair of taxes, we no that global warming is reel and that electric cars emmitt zero greenhouse gases, the worst of which is hydrogen. Vote democrat and are campis will continue to prospre