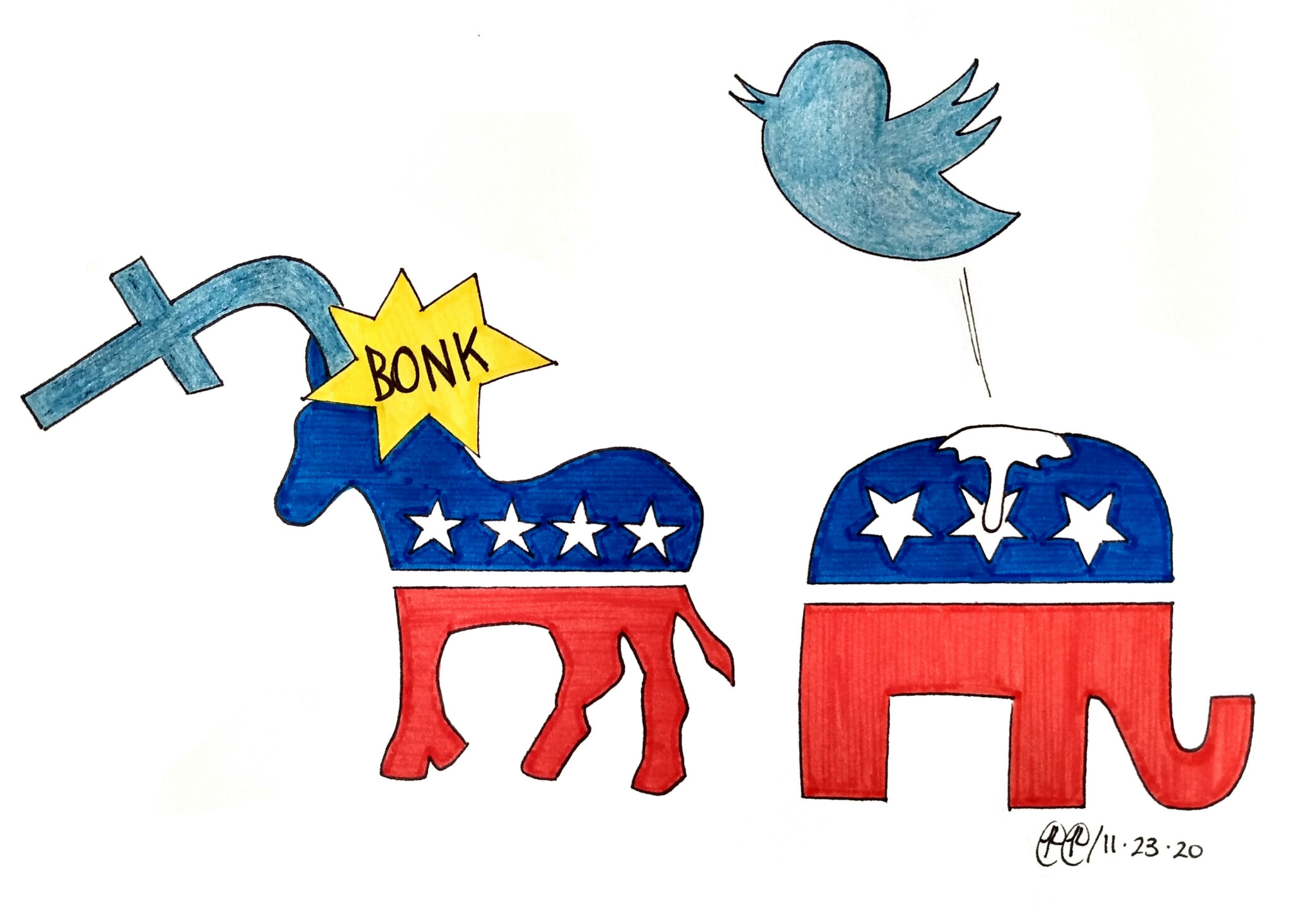

For a country that prides itself on honest conviction and unity, the U.S. does not appear to be anywhere near that. For what is red and blue about this country but the shades of division and contradiction born out of centuries of unresolved ends and animosity? We are a nation of uncertainty in a country disguised in red-and-blue striped strength. The political rift will only continue to grow if we don’t address the root of the problem.

Amid a pandemic and a contested presidential election, social media has become a vehicle for disinformation and sensationalism. Social media is designed to catch you and not let you go. An innocuous scroll through Instagram turns into a one-hour ordeal. One YouTube video simply turns into 15. A single trending hashtag on Twitter can lead you down a rabbit hole of endless tweets and retweets.

Social media’s success lies in its ability to proliferate ideas. When 145 million people log onto Twitter daily, the voices of the multitude grow stronger than ever, gravitating toward whichever news story warrants the greatest emotional response. Only then do we see those same voices taking shape and sides — essentially, we subscribe ourselves to partaking in a two-sided battle.

According to a 2014 Pew Research study, 27% of Democrats see the Republican Party as a threat to the nation’s well-being, while 36% of Republicans see the Democratic Party in the same manner. Prior to the digital age, cultural values and geography often shaped people’s worldview on topics like health care and immigration. But in recent years, following the widespread use of social media, our scope of understanding has expanded. The collective discourse of millions has entered our living rooms.

Partisan media has been a common respite for Americans for years in the form of yellow journalism and cable news. We are apt to chase information that confirms our own ingrained belief system. After all, sensationalism does not discriminate against deceptive content; rather, it uplifts those voices, making it harder for people to recognize what’s true or false. Sensationalism is, unfortunately, an unintended byproduct of free speech — and, by virtue, social media has only enlarged this fragile system of discourse.

Following congressional crackdowns on monopolistic technology companies like Google and Facebook, the existential threat of their roles in our democracy has intensified. In particular, Facebook has the worst take on banning hate speech.

Take President Donald Trump, who was a dark-horse candidate for the 2016 Republican presidential nomination when he championed a now-deleted press release in a Facebook post on preventing Muslim immigration. He called for “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States,” suggesting that Muslims “have no sense of reason or respect for human life.” According to Facebook’s Community Standards, Trump’s post is distinctly a hate speech: a “direct attack on people based on what we call protected characteristics — race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, caste, sex, gender, gender identity, and serious disease or disability.”

The post was not taken down. What was Facebook’s reasoning? “Don’t poke the bear.”

We must challenge our civil discourse by acknowledging each other’s viewpoints regardless of whether or not we agree with them.

The deep divide in today’s political diaspora has fueled a feedback loop between people’s inherent identities — concerning religion, race and class — and political institutions, according to Ezra Klein’s book “Why We’re Polarized.”

The core relationship lies in the media and politicians’ decisions to steer the public using polarizing tactics toward certain viewpoints, including mass media and campaigns highlighting polarizing views. People then absorb these views and respond in a more divided manner than before, thus motivating institutions to create more polarizing policies and strategies. This cause-and-effect relationship becomes, more or less, an endless loop.

As the pandemic shifts much of our political discourse online, people have found refuge in “echo chambers” on social media, in which most of our feeds cater to a single, customizable hub of like-minded individuals. What makes it “echo” is that sites take what we browse and “like” and bounce similar information back at us, so our beliefs are constantly being affirmed by what we see.

This creates a frame of reference in which we are content with seeing content that affirms our beliefs and becomes frustrated with what goes against our inherent views. According to NBC News, social media algorithms are set up in a way that reduces our ability to empathize with those holding opposing views and hinders the quality of authentic dialogue.

Although social media companies are quick to blame, they need to be held accountable by our leaders and media watchdogs. This means that Congress should have considerable leverage in enforcing measures to curb hate speech and disinformation found on social media sites. And, as agents of change, we also have a role to play.

We must challenge our civil discourse by acknowledging each other’s viewpoints regardless of whether or not we agree with them. Reconsider books, podcasts and local newspapers that invite you to look deeper into subjects outside of your comfort zone and gain a new perspective into alternate views. While it’s easy to fall into the trap of mindless scrolling and seeing the same prevalence of opinion, we must foremost question whether our viewpoints are born out of fear or substantiated evidence.

Melody Chen discusses the impact that social media companies have on political discourse as fuel for unresolved tensions between party lines in the U.S.