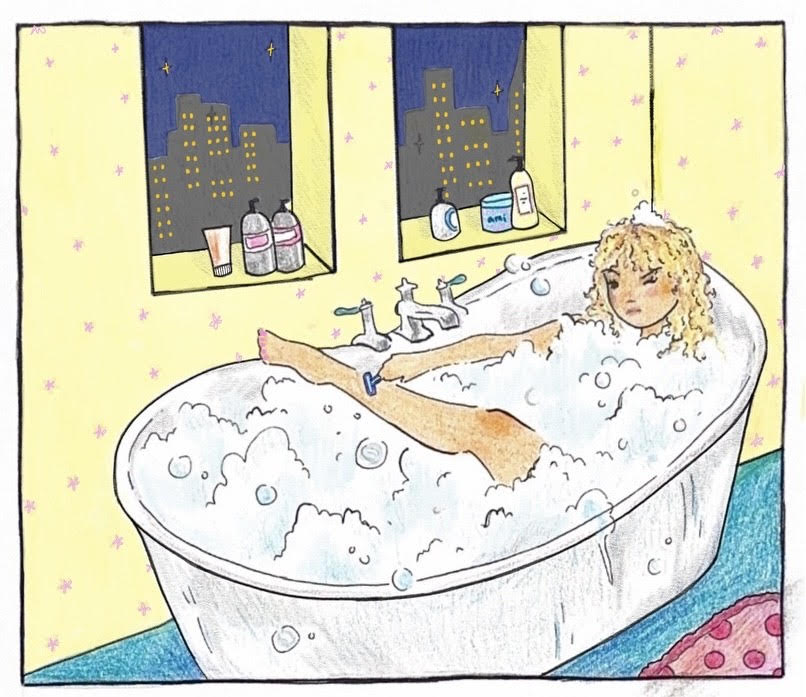

BAILEY LEE / DAILY NEXUS

I vividly remember the first time I ever shaved my legs. I sat in the bathtub as my mom and older sister stood outside and directed me. My sister told me to shave in the direction of the hair, because shaving against it gives you a closer shave but is worse for your skin. I shaved against the hair.

I remember my mom telling me that I only had to shave if I wanted to, seeming a little bit concerned by how excited I was. I often wonder how old I was when shaving became mandatory in her eyes. Now, my mom is always sure to remind me that if I’m going to show certain parts of my body, then they have to be hairless.

I don’t blame her, or anyone else, for believing that shaving is a mandatory part of being a woman. We aren’t used to seeing women with body hair, and removing it is baked into the routine of almost every woman I know.

I was raised with the classic immigrant scarcity mindset, which compounded with my leftist politics as an adult to make me a staunch anticonsumerist. So, regularly buying disposable razors never really sat right with me. In an effort to reduce the amount of waste my hair removal caused, I bought a safety razor and pack of blades my freshman year. It seemed like a great idea — there was no plastic waste, only a small sheet of steel. It was significantly cheaper and the handle was a one-time purchase, which helped ease my concerns about contributing to an industry that I don’t entirely believe in.

However, there’s a reason safety razors lost prominence. It’s almost impossible to cut yourself deeply with a regular four or five blade razor, but with the safety razor it was a regular occurrence. To shave without nicking yourself, you have to move very slowly and intentionally. It took so much time and effort that my shaving days naturally grew further and further apart. And in that time, I got used to seeing myself with hair and letting other people see me with hair.

I initially stopped shaving consistently because of laziness and environmental guilt, but over time, it transformed into a very intentional decision based on my politics around beauty as an institution. Beauty is undeniably oppressive to women. We are taught that it’s a way to seek power, but as sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom wrote in her essay “In The Name of Beauty,” “Beauty is not good capital. It compounds the oppression of gender … it costs money and demands money. It colonizes. It hurts. It is painful. It can never be fully satisfied. It is not useful for human flourishing.” The expectation of being hairless is a particularly egregious example of these points. It costs huge amounts of money over the course of a woman’s life. It often causes women to put themselves through acute physical pain. And all that effort is put into something that isn’t ultimately important to “human flourishing.”

I want to challenge the notion that any opinion that places a value judgment on a woman’s actions is antifeminist. If beauty “compounds the oppression of gender,” you can’t really call yourself a feminist without making any attempt to reject beauty standards. It follows, then, that any serious feminist should attempt to become comfortable with their body hair, even if it isn’t the easiest choice to make. Choice feminism is inherently deradicalizing — if your feminist framework uplifts all choices equally then it doesn’t really stand for anything at all. Michaele Ferguson describes this concept in the paper “Choice Feminism and the Fear of Politics,” much better than I ever could: “Choice feminism also relieves us of the burden of being consistently feminist ourselves: we do not have to struggle to bring our own personal lives into line with a demanding set of principles, because the only relevant principle is that our personal arrangements be freely chosen — and it is dangerously easy to convince ourselves that what we do is a simple matter of free choice.”

Cottom reinforces this point, that a woman acting in accordance with her aesthetic preferences is not necessarily acting in favor of the feminist cause: “Beauty would be a useless concept for capital if it were only a preference in the purest sense. Capital demands that beauty be coercive.” I understand that most women aren’t forced to shave, it’s a choice they make because it’s generally more comfortable to move through the world shaven. But it’s impossible to challenge an oppressive society without going against what you find comfortable. Capital benefits when we believe hair removal is a natural, necessary part of being a woman: it promotes chronic consumption and is now the backbone of an entire industry. If you think that this is something to work against, then refusing to remove your hair is a genuinely radical and effective way to take political action.

What we consider beautiful is so baked into our societal structure, it’s hard to believe that oppressive beauty standards aren’t a necessary part of the culture. But, in the spirit of Ferguson’s piece, which argues that “reimagining our personal lives is an essential component of a feminist reimagining of the world we share,” I invite you to try to imagine a world where we don’t value certain bodies above others. What choices would you make every morning? How would you interact with the people around you?

I can’t tell you with certainty that such a world is possible. But, I think even if it isn’t, it’s worth working towards. As writer Ismatu Gwendolyn asks in their reflection on Cottom’s essay, “What compels us to create a norm for something that was here before we thought up cages for ourselves and our neighbors?” With that framing, it feels like this world, filled with oppressive beauty standards, is no more logical than another world without them.

I am painfully aware, however, that it’s exhausting to carry the weight of the patriarchy at all times, and it’s okay to fail. Even now, the tangible task of picking up a razor feels infinitely easier than the mental load of walking out unshaven. I’ve always admired people who do whatever they want and don’t really care what anyone thinks. I am, however, not one of those people. I care deeply about what others think of me, but I value alignment with my morals over alignment with the status quo. And there’s a different type of confidence that comes with that. It’s a confidence that takes a little bit more effort to build, but it is ultimately much stronger than the illusion of confidence that you get by blending in as much as possible.

And I’m not saying I threw away all my razor blades — I definitely do shave every once in a while, usually when I’m going to a less familiar environment or a more upscale event. I don’t like that I feel the need to do that, but I do. Gwendolyn admits a similar experience in their essay: “I started making negotiations between what I knew to be fair and the life that I wanted when I was seventeen and plotting a way out of the suburbs of Arizona … We are still negotiating, me and this body that breathes.”

I don’t judge women who feel like removing their body hair is necessary to chase the life that they want, but I do wish women would enter thoughtful negotiations with themselves instead of just believing that hair removal is absolutely necessary. Hypocrisy is often considered weak, but I think it takes bravery to accept fault and continually try to be better. If you never contradict your own politics, then you aren’t thinking radically enough.

While writing this article, these negotiations took up more of my brain space than I’d like to admit. And while deeply considering the implications of removing or not removing my body hair, I was reading “Everything I Know About Love” by Dolly Alderton, where she said something that seemed to be speaking directly to me: “Volunteer at a bloody women’s shelter if you want to be useful, don’t spend hours debating the politics of your pubic hair.”

Recently, another seemingly unrelated book gave me a response to this sentiment — “Surface Relations,” by Vivian Huang. I read the introduction for my class on Asian American performance, and I was rather moved by its reference to the paper “Queer Form: Aesthetics, Race, and the Violences of the Social” by Kadji Amin, Amber Jamilla Musser, and Roy Pérez: “to speak of the world-making capacity of aesthetic forms is not a willful act of naivety (though such acts of unknowing have their own value), but a way to keep critical practice vital and resist the downward pull of political surrender.”

The book and paper are both more about art and performance, but I think the aesthetic form of the everyday is equally politically relevant, if not more so. As much as I’m comforted by the idea that the patriarchy doesn’t take particular interest in my body hair choices, I don’t really believe it. There’s a huge range of action that’s politically useful, and critically analyzing the way you play into oppressive beauty standards is absolutely on that spectrum.

I also resonated with the idea that “acts of unknowing have their own value.” My friends often tell me it’s naive to believe that individual acts have any power, which is an understandable reaction to the complexities of the oppressive systems we live under. However, I think that faith in your personal power, even if its an “act of unknowing,” is empowering to the individual — so many people feel lost and hopeless in the face of injustice, and I truly believe that if they made a genuine effort to assuage the injustices they see, it would help them build confidence in a better future.

Beauty is an all-consuming, ever-present force in our lives, and it could be discussed infinitely. I’ve hardly touched on race, which is a huge part of this discussion — especially given how much theory I pulled from Black thinkers reflecting on their racialized experience of beauty. I didn’t touch on desirability under the male gaze. I didn’t even begin to discuss ideals around hygiene and how an exaggerated view of what makes something “clean” begets consumption. I didn’t get to argue that women are expected to be hairless as a means of exaggerating sexual dimorphism, which just reinforces the gender binary. I could keep going! But I’ve already gone on for almost 2,000 words, so I’ll simply ask that you forgive me for any oversimplifications or omissions.

I’ll leave you with this — I only became convinced of the significance of personal choices when my roommate, who doesn’t spend hours debating the politics of her body hair, said to me while getting ready to go to the gym, “the only reason I’m not shaving my armpits in the sink right now is because you’re my roommate.”

Beauty standards are powerful, but they aren’t absolute. They can be stretched by what we find normal, and what we find normal is often decided by our immediate surroundings. Refusing to remove your body hair is a way to outwardly reject one of society’s most stringent and labor-inducing beauty standards, and it can therefore be a material step towards our collective liberation.

Sneha Cheenath would like to apologize to the feminist cause for shaving her entire body the day before Deltopia.

A version of this article appeared on p. 20 of the April 24, 2025 edition of the Daily Nexus.

Growing up, I was always told that shaving was a necessity for women, but as I got older, I began to question that narrative. Embracing my natural body hair has been empowering and has allowed me to challenge societal norms. It’s a personal choice, and I believe everyone should have the freedom to decide what makes them feel comfortable. If you want to explore different hair options, you always can contact Luvme Hair for their range of wigs and extensions.