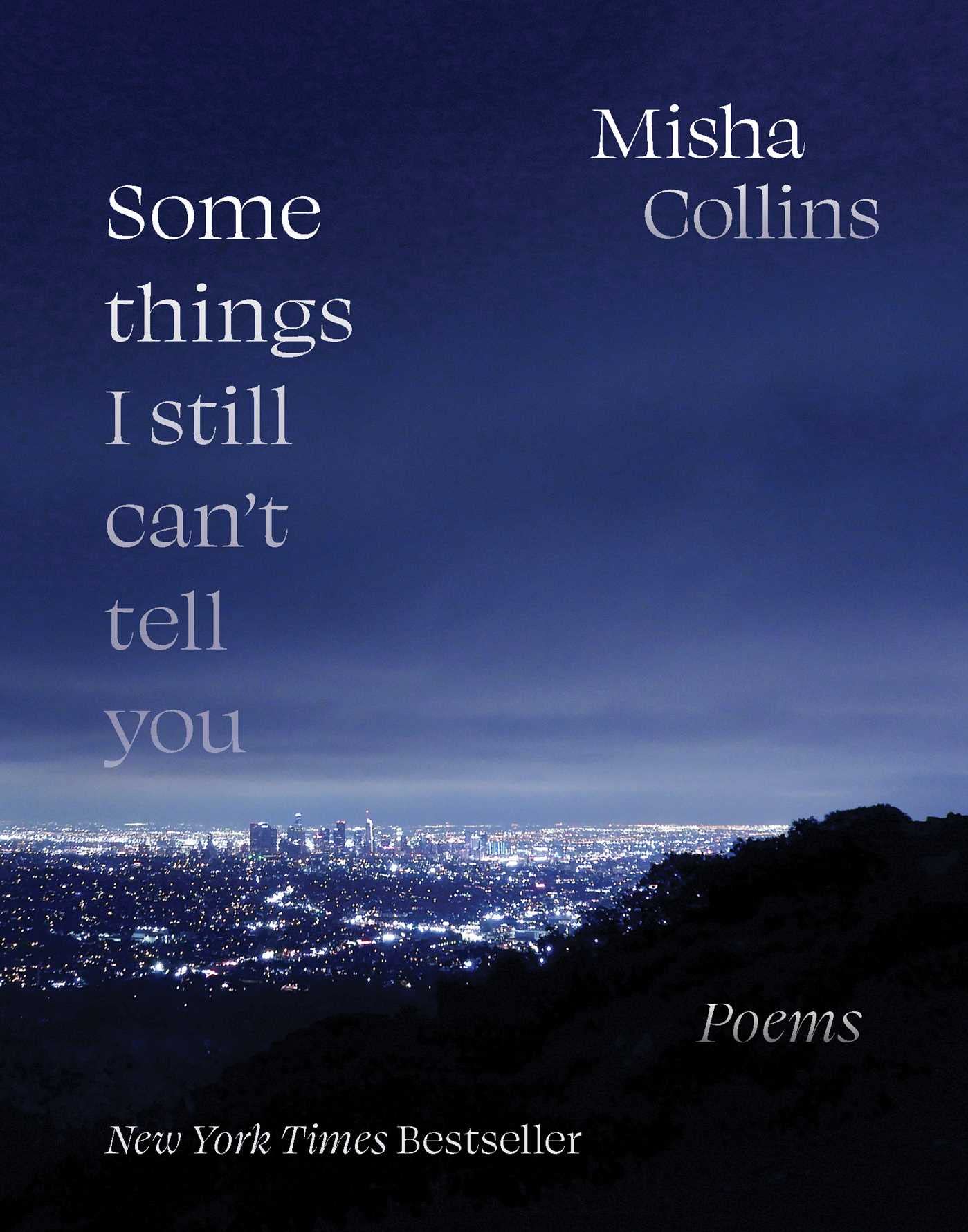

What happens to actors when their career-defining, 15-season television show comes to end? As Misha Collins proves with his first published poetry collection, “Some Things I Still Can’t Tell You,” something quaintly beautiful happens. “Some Things I Still Can’t Tell You” dropped in October, showcasing a menagerie of short, sometimes pithy poems from the actor’s life.

Split into five sections, Collins’ deeply personal collection systematically covers love, loss, lust, childhood, parenting, the joys (and dangers) of jogging in Los Angeles and the disintegration of a long-term romantic partnership. The collection sometimes staggers, but always follows up its weaker installments with truly heart-melting pieces. This leaves a general impression of organized chaos, fitting for a collection covering so many years of what is clearly described as an eventful and dramatic life.

In his poems, Collins slowly and painstakingly builds his own little world, inviting readers in for brief, often uncomfortable, perusal. The most striking aspect of this world is the enchanting, almost angelic characters he brings to life. Chance encounters with strangers on the sidewalk who tell him to “Be HAPPY,” former readers of secondhand books who underlined inspiring passages in red ink or elderly bartenders who offer a moment of kindness spring to life with surprising clarity.

One of the most impressive entries in the collection, “MEN IN WOODS,” adeptly reflects on homosocial friendship in the modern age, so clearly describing the excitement of a growing bond that the reader feels as though they, too, are walking in the woods that Collins and his pal explore.

The collection sings as a complete work, with contrasting pieces placed in immediate succession to allow the reader to experience the rapid-fire highs and lows of modern life, as viewed through Collins’ eyes. I was particularly struck by “FIRE AND WATER,” two tales of running through wildfire, split by ten years and appearing in two separate sections of the book. Of course, like all poetry collections, it’s also an enjoyable read out of sequential order, and I often found myself picking up the book to quickly read one of the poems and mulling over it for hours or days afterward (at least with the more potent entries).

Collins tweeted shortly before the collection’s release that one poem was supposed to be from the perspective of Castiel, Collins’ much-beloved character on The CW’s “Supernatural.” Though this reader could not spot this change of perspective, “Supernatural” appears implicitly throughout the collection, in tales from life on set and in hotel rooms, presented mostly as a wedge between himself and his young family. Of his frequent absence from his children’s home, he asks himself, “What have I missed?”

In one accurately titled “THE LAST POEM,” he poignantly reflects, “One night soon they will sigh their last / Sleeping breath of childhood / And when they do / I want to be pressed close and alert / To breathe it in and hold it / In my body forever.” This visceral description is characteristic of many of the works in the book, making it a sometimes uncomfortable, but also deeply truthful read.

Collins reckons with his newfound wealth, reflecting on a childhood of poverty and the apparent discomforts that come of now having considerable means. These pieces maintain a strong self-awareness, with the author admitting outright which things he struggles to admit, such as in “The Driver,” where he writes, “I have a man, paid for by Warner Brothers, / Who drives me to work. / See that?! I didn’t want to say it… / I HAVE A DRIVER.” Collins never lets the reader be harsher on him than he is on himself.

Themes of directionlessness, pointlessness, loneliness (and many other ness-es) crop up, though the poet avoids coming across as self-pitying, aiming instead to comment on the universal struggles of personhood through the lense of his personal experiences. These poems express the kind of self-awareness that can be detrimental to the psyche, a self-awareness that Collins reinforces with the often self-referential lines of his poems. Several of the poems, like “BLACK CAT” and “IN MY HOTEL BED” are about poetry itself, giving the collection a meta-awareness that feels distinctly postmodern.

For fans of Collins, this collection offers a new, intimate look at a public figure, and for fans of poetry, this collection offers many delectable bites of grounded lyricism and visceral imagery. Though the “You” of the title, lifted from the final stanza of “SUN AND SHADOW,” ostensibly refers to Collins’ partner, I closed the book feeling that there were still some things, nay, many things, that Collins still cannot tell his readers, though he has made a good start.

Rating: 8/10