The nervous energy was palpable as the unfaltering beats of hip hop music blasted throughout the room.

Kai Goh could feel the anxious jitters as his turn approached, but he ignored it as best as he could. Instead, he focused on visualizing the moves he would make.

Goh was competing in King of the Hill, the first tournament hosted by UCSBreakin’ in Robertson Gymnasium on March 9.

Students founded UCSBreakin’ in 2010 for those passionate about breaking and growing the hip hop scene in Santa Barbara. Although it started with only two members, the club has continued to grow. Today, part of the club functions as a squad with two houses for dedicated club members who dance together.

Having danced for a little over five years, Goh knows how important preparation and hard work are when it comes to doing well in competitions. He practices year-round for tournaments and works for months to perfect certain moves.

Goh has been practicing his latest move, the “air flare,” for a little over a year.

As Jonathan “Eugène” Yan, second-year economics and accounting major, puts it, the move requires performing a succession of “one-handed handstands” by “jumping” with your hands while rotating your entire body.

Goh has made a vow not to cut his hair until he has mastered it.

“We party together, we have barbeque together … We’re just a family. Everyone is close to each other, and we try to make sure everyone feels welcome,” said Daniel Setiawan, fifth-year chemistry major and vice president of the club.

Newcomers share the sentiment.

Melinda Guo, first-year film and media studies major, mentioned how supportive everyone in the group has been since she joined.

“[It’s] like a family sharing the passion,” Guo said.

According to second-year sociology major Rusbel Angulo, the core values of hip hop incorporate peace, love, unity and fun, but it isn’t always perceived this way.

Breaking started in the early 1970s as a subset of the hip hop movement. Other elements of the culture, Angulo said, include deejaying emceeing and graffiti art.

“Poverty was pretty much at a rise, and black and brown folks had nothing to do but the art,” Angulo said. “The art was really their self-expression and their way out from the negativity out in the world.”

Brandon Louie, fourth-year sociology major, added that knowing the art’s history and reasons behind its creation are also important.

As breaking began to gain traction in New York and other places in the world, the term “breakdancing” became synonymous with the dance.

According to Angulo, the media soon picked up the movement, but it frequently portrayed breaking as being associated with “drug abuse, violence, thug gangster rap.” He said companies have purposefully constructed it to be viewed this way.

“If you think about it, these people who have been in the hip hop game, they’ve had zero dollars,” Angulo said. “And when they’re able to use this art form and profit off of it, a company can say, ‘Hey, say this and we’ll pay you this many zeroes,’ and when you come from a community that’s been in poverty for so long, money can really go a long way.”

“Breakdancing” is considered a negative term in the breaking community because, for many breakers, the word brings back memories of inaccurate portrayals that they believe have now become disconnected with hip hop culture.

“Right now, we’re in a time period where hip hop is now not just for black and brown folk, but it’s a voice for everyone,” Angulo said. “It’s giving the people the ability to express themselves and have the freedom that they may not have in a regular societal setting.”

In the breaking scene, the way in which breakers influence each other — from unique moves to fashion trends — allows people from around the world to connect with each other.

“You can go out anywhere in the world; with people who have access to brand clothing, you see people who have access to Adidas soccer sweats, wearing Adidas shell-toes … and that’s because the people who popularized it were influenced by hip hop culture,” Angulo said.

“The original b-boys were wearing Adidas pants, they were wearing shell-toed shoes, they were wearing denim jackets … That was the big fashion statement that has arrived today,” he added.

Breaking separates itself as a dance form in many different ways. Yan explained that while several moves have originated from older styles, breaking has brought unique aspects of its own.

“We have things from gymnastics,” Yan said. “A lot of people you’ll see will be doing something that trickers do, like flips, freezes, that kind of stuff. It’s a very unique style that meshes a lot of physically taxing things together.”

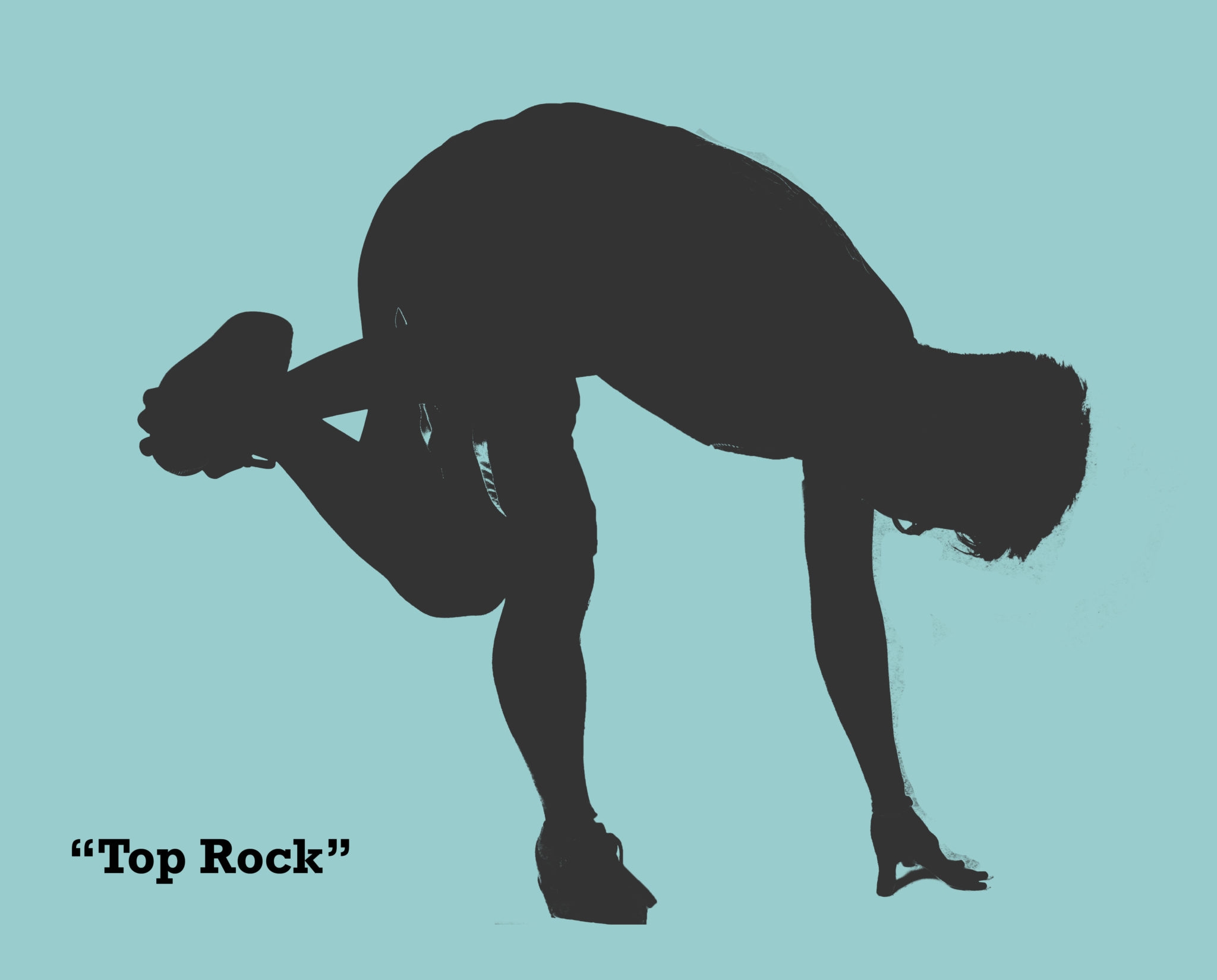

This style requires every breaker to utilize four fundamentals, or foundations, in order to build a unique combination: toprock, footwork, freezes and power.

Toprock describes a breaker’s initial movement in the standing position. While matching moves with the beat of the music, breakers typically make moves that require them to cross their legs back and forth.

According to Yan, toprock is the “entrance” of the breaker.

“The traditional format is you [can] literally just walk in on the beat and that’s when you’re supposed to show your character, personality, how well you can groove,” Yan said.

Footwork refers to breakers’ foot movements on the ground. With only their hands and feet, b-boys combine moves like “six-step,” a step with six movements, into one fluid motion.

“It’s the older kind of thing that differentiated breaking from several other dance styles because you would see breakers staying on the ground for a lot longer doing steps and taking a really long time to get back up,” Yan said.

Freezes are the “picture” moves for breakers. These are the moves that breakers hold for a few seconds.

“Freezes are supposed to be the period to the sentence of a [combination]. A freeze is something that you can end on. They can be really complicated in terms of athletic ability, or they can literally be posing for a second and taking a moment to breathe,” Yan said.

Finally, power moves are the “flashy” part of breaking; these are the bold, dynamic moves that typically involve rotating and tend to elicit responses from the audience. Moves like the air flare are considered part of this category.

According to Yan, many power moves are influenced by other dance styles. “Flares are borrowed from gymnastics, and in return when we made it [into] an aerial equivalent — which was the air flare — they kind of borrowed it back,” Yan said.

However, these fundamentals change based on who you’re asking. According to Louie, the fundamentals for an “old-school” breaker are not the same for a contemporary one.

“If you’re asking a new-generation kid, he might say the fundamentals are toprock, footwork, freezes and power moves, but to an old-school person, they’re going to say that it’s footwork and toprock, and then they also add a different part of dance called uprocking. As the dance evolves there are more styles coming out, there are more different kinds of moves coming out that people want to try, so it can get kinda confusing,” Louie said.

Although the definition of fundamentals may differ, each unique combination of fundamentals creates a set, and the sets can define the dancers themselves.

According to Goh, his favorite fundamental to practice is power moves. However, he says that it is important not to disregard the other fundamentals.

“[A] lot of people don’t realize how much work people put into all the other foundations because footwork can be just as tiring if not more exhausting than power, but it looks very intricate and only people who know what to look for can see those details. People who train in those respects like footwork and toprock … and try to develop their style over their power don’t get as much credit as they should,” Goh said.

Nicknames also play a supporting role in the breaking community. According to Setiawan, b-boy names can be made up or given to you by others. However, names aren’t necessary when you’re first starting out, and there’s no rush to create one.

“My b-boy name is Set One, and it was actually really funny because my last name was Setiawan. And when I first danced in high school a lot of my friends would make fun of me. They would be like, ‘Oh you know Set One cause he only has one set!’ But it grew on me. I took it, I started competing with it, and then I built a name from it, and I actually ended up liking it,” Setiawan said.

One of the misconceptions of breaking is its intensity, according to Yan. He said it’s easy to jump to conclusions watching breaking sessions because it can look closed-off or cliquey.

“You see it and you think, ‘Wow, everyone is so intimidating, and they’re so focused and so aggressively training,’” Yan said. “It’s because everyone is a student in the end. Everyone is trying to get better.”

Yan tries to stress inclusivity in the dance classes he leads at UCSB’s Recreational Center and at a nonprofit organization committed to teaching dance to underprivileged youth called Everybody Dance Now!, which he teaches with Goh. The class environment is specifically geared to help people overcome their fear of performing in front of an audience.

“It’s very scary to go up in front of other people, especially doing something that they know really well,” Yan said.

According to Goh, overcoming stage fright on the dance stage translates to other activities as well.

“Through this dance, I learned how to be confident … because if you look like you know what you’re doing then [the judges are] going to think like you’re know what you’re doing,” Goh said. “So I just take [that] and project it to my own life.”

Angulo said that UCSBreakin’ aims to grow the hip hop community in Santa Barbara to the size of those in San Francisco, a city in the Bay Area whose Facebook group for breakers, Bay Area Cyber Cypher, is 1,700 people strong.

Still, Louie said that breaking is much more appreciated in places like Germany — the origin of the international breaking competition Battle of the Year — than in the U.S.

“Hip hop’s here to stay,” Angulo said. “Hip hop won’t stop. It won’t die. It’s only going to get bigger. It’s only going to get better, and we are the future, and with that said we will decide how this future will form.”

Not everyone recognizes the culture behind breaking. According to Goh, many see the name of breaking as a movement, focusing only on the acrobatics instead of thinking of it as an art form.

“Every time you go on that floor, it’s a new canvas,” Goh said. “It’s blank and you paint it yourself with what you have using the foundations like anything else.”

After minute-long battles in a Seven to Smoke format (two members dance-off at a time; seven wins calls the battle), the judges eventually declared Kai Goh the winner of the first King of the Hill tournament. About his win, Goh said he hopes the tournament will encourage the rest of the members to work harder for the next one.

“It brings out the best in people when you battle them, and you put your 100 percent in, they have to put their 100 percent back in order to try to beat you,” Goh said. “So I like using my energy to bring the best out of them. Winning is great, but what I want them to do is go home with that L and then turn that into a W if they can next time.”

Besides competition, Goh also said self-expression and a sense of community help drive this passion in breaking.

“Arts like these allow you to express yourself in new dimensions,” Goh said. “And I’m sure many people can relate to this, but when you put yourself out there, whether it be on paper, on the floor or to [the] music, it feels good to be recognized by other people and just to share what you make. So breaking is just another form of that, and it feels as good as cool as it looks.”

A version of this story appeared on p. 6 of the Thursday, April 6, 2017, edition of the Daily Nexus.