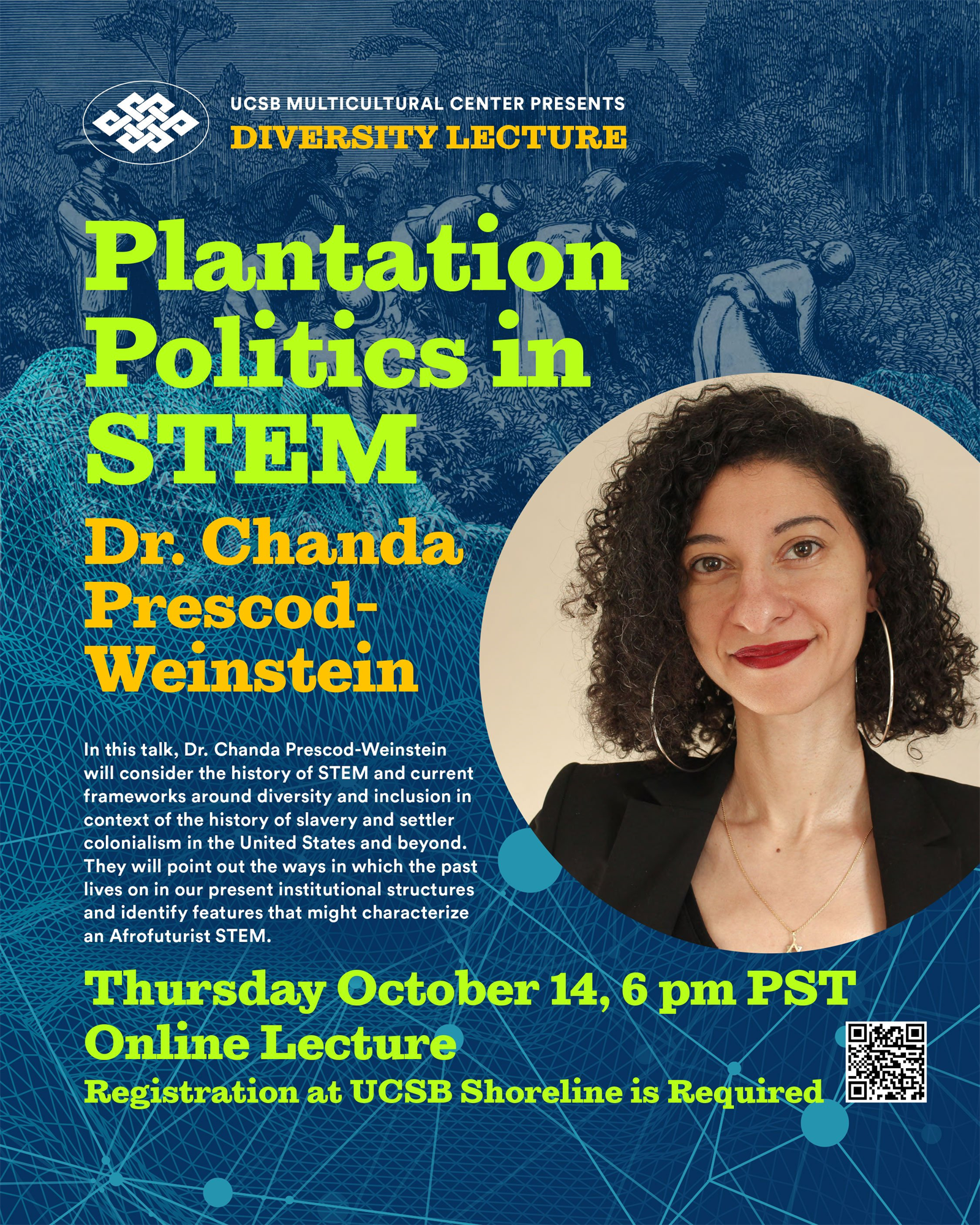

Theoretical Physicist and Assistant Professor at the University of New Hampshire Chanda Prescod-Weinstein spoke about the intersection of science and racial diversity at her lecture on Oct. 14, hosted by the UC Santa Barbara MultiCultural Center.

Prescod-Weinstein said that without substantive efforts to accompany conversation, diversity initiatives serve as “cheap substitutes” in place of “materially changing the conditions that marginalize people.” Photo Courtesy of UCSB

The talk, titled “Plantation Politics in STEM,” covered the history of racism in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields through the lens of colonialism and pinpointed the ways in which underrepresented minority faculty, like herself, still experience the perpetuation of white supremacy in academia.

“White supremacy is embedded in scientific practice,” Prescod-Weinstein said.

As one of 100 Black women in the United States ever to receive a Ph.D. from a department of physics and the first Black woman to hold a tenure-track faculty position in theoretical cosmology or particle theory, Prescod-Weinstein said she has engaged in activism for equality in science and in Black feminist scientific research throughout her career.

She added that it is important to acknowledge and address the historical and contemporary phenomena that contribute to inequities and shortcomings in science.

“Part of the lesson is that science is shaped by the stories we tell about who matters and whose ideas count,” Prescod-Weinstein said.

She emphasized that the work of unnamed Black engineers, midwives, agriculturalists and plant biologists is what led to her and other scientists to exist in a predominately white space today. In addition, she said that current stereotyped attitudes about race create barriers and dissuade underrepresented minorities from participating in science.

“[I’ve heard things like] ‘Black people aren’t interested in science. Black people don’t have a culture of science. Black people just don’t care about school. Latino people care more about family than education,’” Prescod-Weinstein said, describing racist claims she has encountered in the past.

The professor also discussed the “persistent” lack of trust between the Black and scientific communities, especially in interactions with doctors. She related this tenuous relationship to a historical pattern of medical practitioners violating the bodily rights of Black individuals, such as when the founding father of modern gynecology operated on unanesthetized and enslaved Black women.

According to Prescod-Weinstein, modern attempts to rectify the exploitation of Black people and their expulsion from white-controlled spaces have relied on opening dialogues around diversity and inclusion and increasing underrepresented minority (URM) representation in educational institutions.

However, without substantive efforts to accompany conversation, she said that diversity initiatives serve as “cheap substitutes” in place of “materially changing the conditions that marginalize people.”

“The problem with diversity and inclusion discourse is that it asks us to live in a box where people are still getting killed,” Prescod-Weinstein said. “Talking about diversity and inclusion will not prevent another Tamir Rice from being murdered in the park. It will not prevent another Aiyana Stanley-Jones from being murdered on her couch.”

Prescod-Weinstein experienced first-hand how educational institutions use strong diversity rhetoric to maintain legitimacy while tokenizing their URM faculty. She recalled how the director of the institute at her graduate school asked her to deliver a major presentation, using her appearance to project a more inclusive image of the university despite her experiencing “severe racism” while studying there.

According to Prescod-Weinstein, this exploitation of Black people and Black labor helps universities appear diverse while devaluing Black voices.

“They’re not actually there for you. They’re just trying to contain you,” she said.

In addition, Prescod-Weinstein described the unique responsibility of delivering visiting lectures on race and diversity at other universities. At those events, marginalized students would approach her to speak about the racism and trauma they experience within their education, an emotional burden that her white colleagues do not typically face.

“Because I [was] assigned female at birth, because I am Black, I get asked to meet with marginalized students, and I get asked to [speak] for free,” Prescod-Weinstein said. “I would go home and cry [after hearing students’ stories].”

Prescod-Weinstein said finding a supportive network of people is proving critical to facing microaggressions in the field and handling adversity.

“I handle it in community with other people, and I handle it by fighting back,” she said. “That’s part of how I survive. I don’t take it quietly.”

In the past, Prescod-Weinstein said she would lose sight of the social value of her work, as her research seems far removed from the efforts of grassroots racial justice movements. She recalled once wondering why she was spending time working through quantum field theory calculations while her mother was in the streets protesting for Black Lives Matter.

In response to her doubts, she said her mother told her the following: “The things that you want to think about matter. The way that you think about the universe matters … People need to know that we live in a universe that is bigger than the bad things that happen to us.”