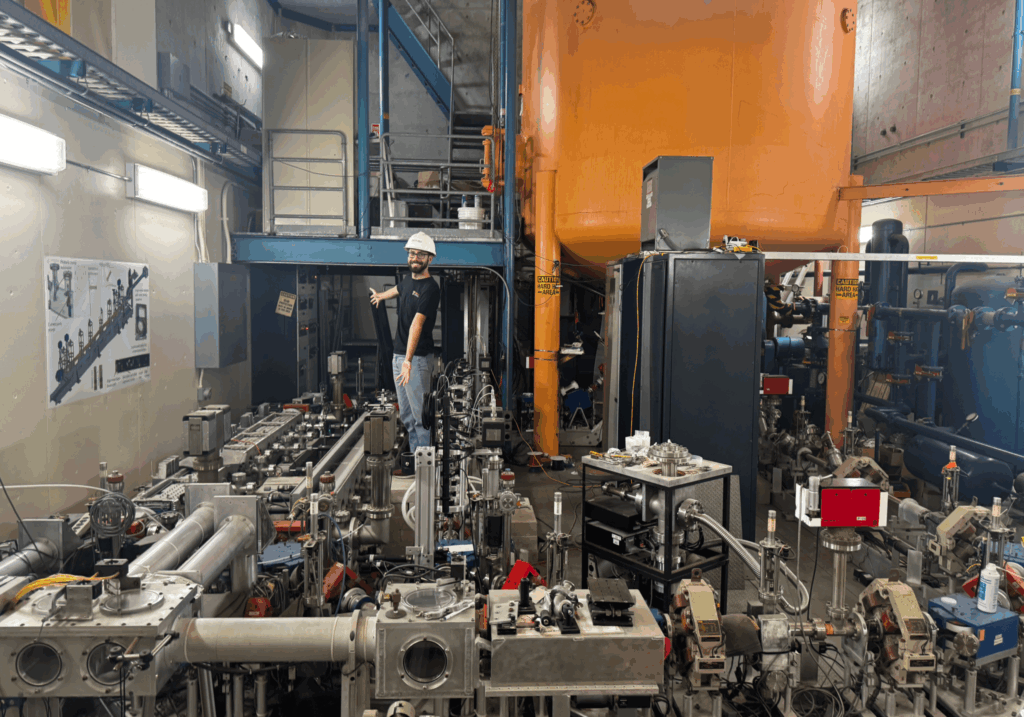

The physics department at UC Santa Barbara houses its own powerful particle accelerator that accelerates electrons to 99.4% of the speed of light. The roughly 10-meter tall accelerator is part of a free-electron laser (FEL) that produces powerful, terahertz pulses of light that the Sherwin Group uses to probe matter at its most fundamental level.

Picture of graduate student Alex Giovannone in front of the FEL.

The UCSB research group has several ongoing projects testing current understanding of fundamental quantum physics in materials, as well as the dynamics of proteins at the molecular level. Their work has applications in quantum computing, biophysics, chemistry and future electronics technologies. The Sherwin Group’s ability to produce short and powerful pulses in the terahertz range — a low frequency region of the electromagnetic spectrum — with their FEL sets their research apart and is instrumental to their ability to probe unique properties of materials.

A typical day of data taking begins by starting up the FEL, using computers to remotely monitor its status until it is running optimally at the right power and frequency. Once the electrons are accelerated, they enter a part of the FEL called the laser cavity, where they are directed through a network of mirrors and magnets. As the electrons pass through strong magnetic fields, they oscillate back and forth generating powerful radiation in the terahertz frequency range.

“There are so many different factors that affect the components of the FEL,” Juan Gaitan, a graduate student in the group, says, describing the typical process of setting up the FEL. “We need to tune it every day and every time, ensuring the power is correct, and depending on the experiment, we sometimes do cavity dumping.” Cavity dumping is a way to let the power build up inside the laser cavity, rather than continually leaking out of the laser, and then releasing to produce short, powerful pulses.

The powerful pulses allow the group to perform electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy, a method to probe electron spin properties. “We are able to look at the magnetic moment of the electron,” Alex Giovannone explains, another graduate student in the lab able to probe states with high resolution. Detecting signals from nuclear spin states is an established technology used in hospital MRI scans, however, detecting and understanding the signal from electron spin states is far more novel and not well understood: “Electrons are much more interactive with each other and with the environment, travelling together in clouds,” Giovannone explains. “One of the things we want to do is study these complicated electronic states.” The group already uses an extremely strong 12.5 Tesla magnet to probe these interesting states, and their new setup will go up to 16 Tesla, more efficiently making use of the FEL’s capabilities.

The FEL’s extremely rapid pulses also allow the group to measure electron excitations with “nanosecond lifetimes,” which has important applications to quantum computing. A qubit — a fundamental unit of quantum information — must exist in a quantum state, exhibiting properties of superposition and entanglement simultaneously, and maintain that state long enough to perform calculations. The time that a system is able to maintain quantum state is referred to as its lifetime, so measuring the “lifetime of excitations” in materials allows the group to meaningfully assess candidates for quantum computers.

One novel candidate is quantum spin liquids — spinons, which the group hopes to measure with their new spectrometer. “Not only is it a really interesting quantum state inside a material, it’s also something whose lifetime has never been measured before,” Gaitan clarifies. “Thanks to the FEL we are one of the only people in the world that could measure that once the spectrometer is built and ready.”

Another important project the group is working on is high order sideband generation (HSG), which is a method to figure out how electrons behave in semiconductors. One laser is used to excite an electron, such that it moves from the valence band, where the electrons are still bonded — leaving an anti-electron hole in its place — to the higher energy conduction band where electrons are free to move and conduct electricity. They can then “hit” the electron with a pulse from the FEL, giving the electron a high amount of energy and causing it to shoot in a trajectory along the conduction band. Once the electron loses energy, it returns to its original place in the valence band, annihilating with its antiparticle and producing light.

One unique ability of the Sherwin Group is to differentiate between the dynamics of the electron when it is excited versus when it is driven. “We use one laser to excite them, and one laser to drive them, so we can see specifically what the driving dynamics is,” Gaitan shares, explaining the aspects of their HSG experiment that makes it unique.

The superposition of paths the electron can take manifests as a spectrum of light emitted when the electron de-excites, separated by twice the terahertz frequency. “Each single emission is one different superposition of paths the electron took.” They are able to tell the dynamics of the electron from its wavefunction as well as the time evolution of the system. “We are starting to do this in unknown materials, where you don’t really know what the electron is going to do,” Gaitan explains, suggesting the broader applications of HSG. “We are also able to tell how long electrons stay coherent. There are devices that manipulate these electron-hole pairs to do quantum computation, so measuring how long these electrons stay coherent tells us whether the material can be used.”

The work of the Sherwin Group uniquely explores fundamental properties of materials, and their experiments and technology have the potential to be applied to a variety of disciplines, including quantum computing and biophysics. With the incredible power of the FEL, the Sherwin Group has a rare ability to probe fundamental properties of materials, advancing the current understanding of the theory behind electrons and matter at small scales.

More propaganda promoting science pornography. No university in the history of the world has betrayed the human species and truth more than UCSB Mafia. And no department at UCSB Mafia has betrayed truth more than its Physics Department. In a time when the need for the knowledge and authority of Physicists has never been greater, the UCSB Mafia Physics Department has disgraced itself instead by sticking its collective head in the sand of quantum irrelevance. All Physicists everywhere should be aligning forces to hone their Newtonian saws to cut down the tree of lies and obfuscation regarding the building collapses… Read more »

This impressive technology allows scientists to explore the very fabric of matter at unprecedented levels. For anyone interested in the intersection of science and technology, you should definitely check out this link: https://highflybet.com.pl/app. The implications of their work not only enhance our understanding of quantum physics but could also pave the way for new innovations in various fields. It’s exciting to witness such breakthroughs and see how they may influence future developments in science.