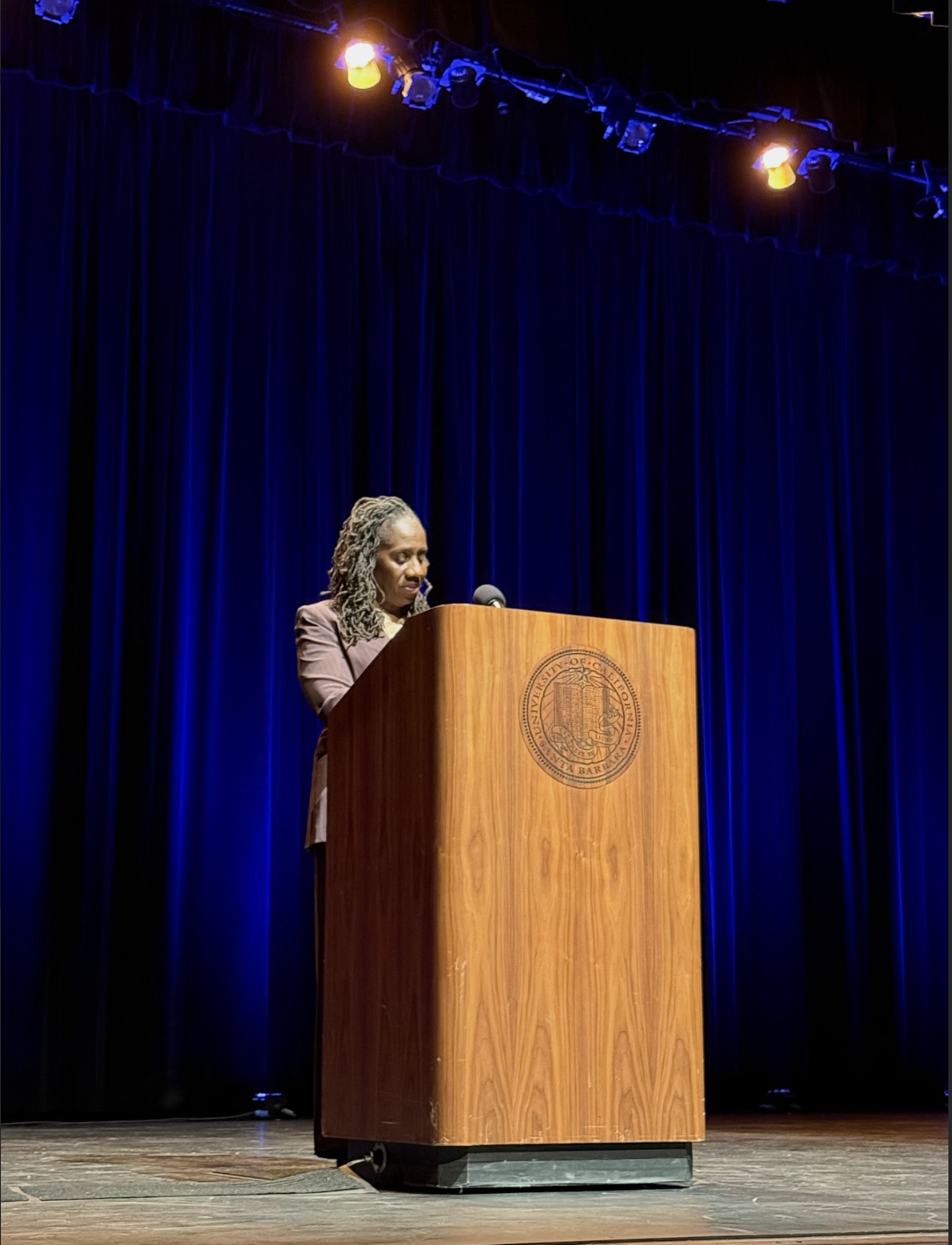

Civil rights lawyer and Howard University School of Law professor Sherrilyn Ifill delivered a lecture on reimagining American democracy at Campbell Hall on Nov. 6 to an audience of around 300 students and community members.

Ifill discussed the importance of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution and also highlighted what she believes is needed to reform American democracy. Iris Guo / Daily Nexus

Ifill, who served as president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense Fund from 2013 to 2022, discussed the concept of citizenship and the role of the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution. She also highlighted what she believes is needed to reform and improve American democracy.

Ifill began the lecture by asking the audience to imagine the rift the country felt in the aftermath of the Civil War.

“600,000 Americans have been killed. Much of the landscape of the country has been decimated. People are trying to find their way home. 4 million Black people who were enslaved now have to be integrated into this country,” Ifill said. “The one man who many and most believe was the one person who could hold together the Union, the President of the United States, President Lincoln, is assassinated in a conspiracy in Washington, D.C.”

She emphasized that, while the war was technically over, skirmishes were still being fought in Texas and other states in the South. During this uncertain period in American history, Ifill said that the “Reconstruction Congress,” which people considered “radical Republicans” at the time, decided to create a legal framework that would promote equality.

“What would you do? How would you stitch together a nation so fractured? How would you create a framework for a multiracial democracy in which those 4 million Black people are integrated into the republic?” Ifill said.

Ifill said she believes the 14th Amendment brought the country together, as it granted citizenship to all people born or naturalized in the U.S. and guaranteed all citizens “equal protection of the laws” and “due process of law” from state governments.

“But just those words of the first sentence of the 14th Amendment, that you are a citizen of the United States and of the state in which you reside, [were] deliberately designed to move front and center our sense of national citizenship. Because after all, it was state citizenship that led to the fracture of the republic,” Ifill said.

Throughout her lecture, Ifill emphasized the importance of the 14th Amendment in reshaping American democracy by making it so every person is “counted as a whole person” for the purpose of representation. The amendment also promoted equality by overturning the 1787 three-fifths compromise, which counted enslaved individuals as three-fifths of a person for purposes of representation. According to Ifill, prior to the 14th Amendment, the word “equal” was not used once in the American Constitution.

“Most Americans know nothing about the amendment that reshaped our national identity after the Civil War, and that the reason you believe that you have the right to equal treatment in this country is because of the 14th Amendment, not because of what Hamilton and Jefferson and Madison did,” Ifill said. “As a matter of fact, there’s no concept of equality in that first Constitution.”

Ifill said the 14th Amendment can serve as a “powerful template” during times of “democratic crisis” because it enables people to believe that they have the power, right and obligation to “re-found” the country as a whole.

“When we are faced with a nation that is unraveling and in which our democracy has been broken, we have the right and the obligation as citizens of this country to become the founders and the framers of the next iteration of American democracy,” Ifill said.

Ifill reconnected this notion back to the Reconstruction Era, saying that individuals during this period faced similar challenges that are still present today — violence, political instability, white supremacy and an “authoritarian president” — which the 14th Amendment helped to overcome.

According to Ifill, many Americans feel “powerless” in contending with the idea of rebalancing “democracy to be like [people] remember it.” However, Ifill said that people should not feel nostalgic for the past, but instead focus on the present.

“Perhaps these are the only moments when everything is collapsing around us, where we can actually be bold enough to create something different — to create the country we actually want rather than the one we have tried to work with,” Ifill said.

In addressing the current American “crisis in democracy,” Ifill said that the second presidency of Donald Trump is an “accelerant” that has exacerbated the preexisting “cracks and the fissures in the foundation of our democracy.” According to Ifill, Americans must reimagine and “re-found” the country to solve this instead of waiting for a Democratic candidate to take office.

“I believe this moment compels us [to see what] we want this country to be, and to be comforted by the fact that this country has been re-founded before. We’re not being asked to do anything that those who came before us didn’t do — I’m only asking that we do it without 600,000 dead,” Ifill said.

The second half of the evening consisted of a moderated conversation with John Park, a professor of Asian American Studies at UC Santa Barbara who specializes in immigration law and policy, race theory, political theory and public law.

Park drew on the 19th century to expand conversation on what Ifill described as a “period of tremendous dynamism.” The two discussed how voting was not part of the original conception of citizenship and how our current understanding of what it means emerged from an extended, strenuous process that was shaped by the efforts of activists and abolitionist figures.

Park highlighted the role of activism and civil disobedience as vital drivers of progress. He specifically stated that many heroes of the 19th century “were often the people who broke the law.”

Ifill also addressed current debates surrounding birthright citizenship, criticizing the idea that it should be a case considered by the Supreme Court due to its explicit protection in the Constitution.

Ifill highlighted the broader idea that every action, even if seemingly insignificant or unsuccessful, contributes to the context that shapes policy.

“Lots of young people will say to me, ‘We protested in 2020 and nothing happened.’ And I say all the time, none of it is wasted,” Ifill said. “You are shaping how we think about these issues. You are shaping the conversation about what is just and what is not just, about what citizens have the right to expect from their country, and what kinds of protections they have the right to expect.”

Ifill concluded by saying universities will continue to contribute to the process of promoting change within American democracy.

“There’s no better place than the university to do that work. To reimagine this democracy, to believe that you have the right, to believe you have the tools, to believe you have the obligation to plant a vision for the future of this country, to plant a vision for a healthy democracy, one in which the foundation is strong and can survive accelerants, can survive strong winds and earthquakes,” Ifill said.

A version of this article appeared on p. of the Nov. 13 print edition of the Daily Nexus.

This country can be “refounded” without the violent necessity of 600,000 dead by being a Nation with every university not having a window unbroken all in nonviolent demand for the long-overdue and still-imperative Independent 9-11 Investigation. Truth can “refound” the Nation. One window nonviolently broken per courageous Citizen starting at UCSB and virally spreading until all university windows across the Nation are nonviolently broken. With a preponderance of evidence indicating that 9-11 was a Zionist job, revelations of an Independent 9-11 Investigation will lead to the recapture of the USA from a strangled ZOG, deconstruction of Israel and the joyful… Read more »

Why are you here – you are a felon who was banned from campus and forced into a psych facility. Everything you say is rambling nonsense. What a POS

Dig down deep @Haskell’s–to the very concrete submerged anchoring of the pier pilings.

Don’t merely mitigate the issue for the short-term–this solves nothing. Advocate for a comprehensive clean-up operation–once and for all.

h

Did you feel the 4.1 earthquake this morning centered near San Luis Obispo? I’m here @my residence in Bullhead City, Az. and I’ve just experienced a torrential downpour from the recent atmospheric river assault. I just got off the phone with my publisher-tech support headquartered in Austin, Texas. We’re in the process of arranging the the thirty-five listed poems in an order that reflects the best value metric possible. It will be out on Amazon in three months for approximately $20.00. Stay tuned! All poems reflect a “poetic alchemists perspective(s).” on a number of different fronts, both political, environmental, and… Read more »

High surf warnings and rip currents issued for the entire western coast of the United States today–a very rare occurrence indeed!