The 1990s was the decade of rock’s most dramatic paradigm shift. With the 1980s being dominated by the pop or “glam” metal that had been coming out of Los Angeles’ Sunset Strip and defined by groups such as Poison and Mötley Crüe, the genre had become enormously popular. By the ‘90s, however, pop-metal had almost become a parody of itself with every rock band having a radio-friendly power ballad in their repertoire … Enter Nirvana. While not the only band to create music that seemed to directly confront the absurdity of hair metal, the Kurt Cobain-led rock group indeed led the charge for alternative bands (especially from Seattle) to thrive.

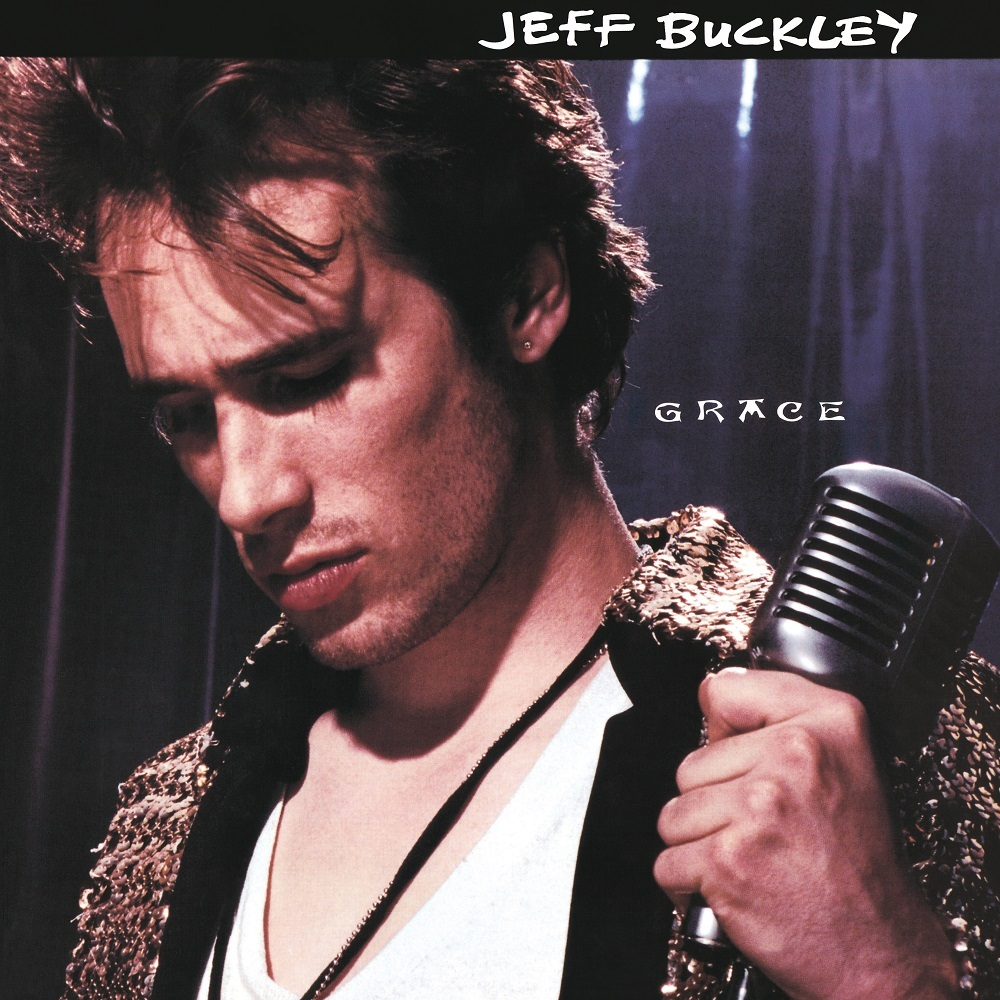

In this backdrop, there was another artist who was quietly changing the music scene by the name of Jeff Buckley. Buckley was the son of ‘70s folk singer Tim Buckley, known for his song “Song to the Siren,” who unfortunately passed away from a drug overdose while Buckley was still very young and left his son with the pressure to live up to the legacy of a man he barely knew. He worked as a session musician in Los Angeles before moving to New York to work in the club scene. In this new city, he began the process of creating the songs that would appear on his first and only album “Grace.”

“Grace” is a 57-minute journey with each song seeing Buckley explore a new musical avenue, his years as a session musician no doubt informing his willingness to experiment in different genres and not simply adhere to the musical standards that would have made him a star in his time. While each song seems to have a different sound, there is a coherence that runs through the album that doesn’t find the changing of songs abrupt. There are “song” songs (“Grace,” “Last Goodbye,” “Lover, You Should’ve Come Over”) that could, and probably should, have been massive hits within their time. But there are also songs (“Mojo Pin,” “So Real”) that would feel more at home on a Tool record than on the Top 100 Charts. However, a song such as “Eternal Life” sounds somewhat dated and reminiscent of the ‘90s grunge scene, with a sound that evokes Pearl Jam.

Interestingly enough, the two covers on the album are also the two quietest songs in the album: “Lilac Wine,” made famous by a Nina Simone cover, and “Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen. “Lilac Wine” comes off as a sort of modern jazz standard with quiet instrumentals and Buckley almost whispering the lyrics, and the whole aesthetic of the song leads one to picture him performing the record in a smoky New York club.

Even if you have never heard of Buckley, you have without a doubt heard his iconic rendition of “Hallelujah” by Leonard Cohen. And for many listeners, this version has become the quintessential rendition of this song as Buckley’s ethereal voice adds a haunting sound that lends to a completely unique interpretation of the classic song.

Buckley’s incredible range and shaky vibrato lead to an immediate comparison to the rock legend Robert Plant (Buckley even performed a Led Zeppelin cover on his album “Live at Sin-é”) yet he seems to have more control and frequently employs a softer sound in comparison to Plant’s siren wails.

Buckley passed away on May 29, 1997, at the young age of 30, the result of an accidental drowning. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he didn’t pass away from copious drug or alcohol abuse, but from simply going swimming in the Mississippi River at night. Among the saddest parts of the results of the guitarist’s early passing is that his influence on music has only begun to be acknowledged through modern artists who recognize him as an influence like pop music giant John Mayer and alternative artist Phoebe Bridgers.

Aside from “Hallelujah,” it is unlikely you will hear any of Jeff’s original songs played, even on throwback radio stations. Nonetheless, his music has stood the test of time better than that of many of his peers and falls in line with the sort of creativity and uniqueness that Nirvana ushered in. Buckley should have been a superstar, but listeners can still appreciate his little body of work for the creative genius it is.