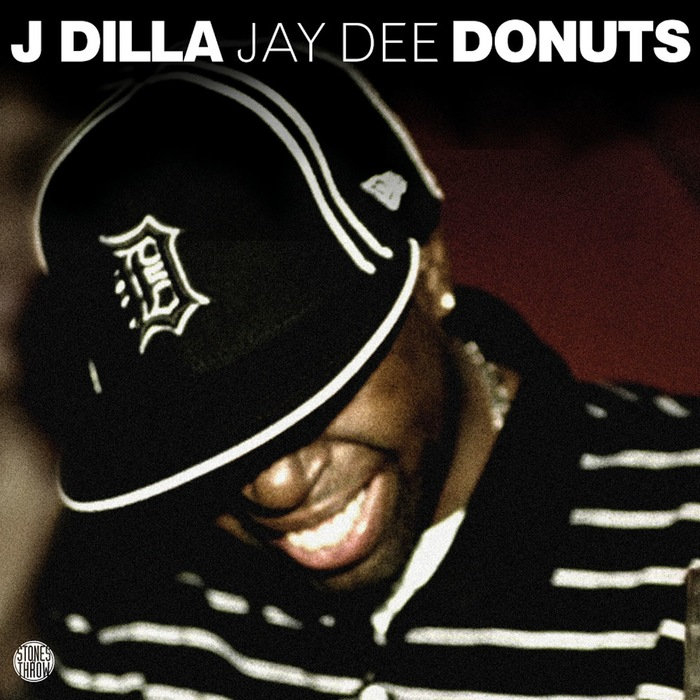

The most inspirational beat tape of all time was created in a hospital. James Dewitt Yancey, better known as J Dilla, released his album “Donuts” just three days before his passing on Feb. 10, 2006. Dilla had previously been diagnosed with lupus and a rare blood disease called thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP); as he sought treatment, Dilla surrounded himself with the comfort of old records and his music production equipment. He fought against his mortality until the last minute, eternalizing his soul in “Donuts,” a parting gift that transcends the art of beat-making.

Dilla had been known for his signature production style for a handful of ‘90s hip-hop groups, most notably A Tribe Called Quest and The Pharcyde. He refused to incorporate quantization, a program that snaps instrumentals into rhythmic place, in his music. Combined with a love of sampling, this conscious imperfection gave Dilla’s beats a uniquely organic feel. Similarly, soft, low-end textures are scattered throughout his work; “Find A Way” by A Tribe Called Quest demonstrates a characteristic-Dilla bassline, subtle and weaving between the drums.

Though “Donuts” is an extension of these techniques, the album’s name appropriately highlights the 7” records Dilla used to craft the project. Dilla harvests the emotional potency of each sample, giving life back to the dusty disks as he stands on the shoulders of giants. Certain motifs, like sirens or distorted vocal passages, glue the project together, but the diversity of samples makes the various songs embody all the emotions of human existence — Dilla’s very own “Songs in The Key of Life.”

Dilla carefully chose how much he messed with his vocal samples. The bass on “Two Can Win” adds a simple yet addictive groove to the tender falsetto of Smokey Robinson and the Miracles’ “A Legend In Its Own Time.” Meanwhile, “Stop” features jagged drums and interruptions to emphasize the assertiveness of Dionne Warwick’s vocals from “You’re Gonna Need Me.” The most maximalist chopping of vocal samples is in “Don’t Cry” — as described by Vox, Dilla initially presents a clean snippet of his subject, “I Can’t Stand (To See You Cry)” by The Escorts. However, a tempo change around the song’s 40-second mark welcomes a kaleidoscope of vocal bits that Dilla astonishingly weaves into a singular melody.

While plenty of sample-based producers traditionally base their work around vocal samples (e.g. Kanye West’s “chipmunk soul” style), Dilla’s “Donuts” has much alternative inspiration. The back-to-back combo of “Airworks” and “Lightworks” offers an industrial feel to the project. Shrill string harmonics and distorted vocals over a plucky beat characterize the former track, while Dilla mashes a fictitious advertisement, what sounds like Mary Poppins’ singing, pulsating sirens and his signature low-end into a dynamic paranoia for the latter. The least accessible track is “The Factory” — a machine-like collage of sounds with a unique march to it.

The ultimate appeal of “Donuts” is Dilla’s talent to share specific emotions using only his production equipment. “One For Ghost” meditates on childhood pain, as a vocal sample recalling physical punishment lingers unobstructed on simple percussion. The feeling of pure joy encapsulated in “The Diff’rence” brings relief to the tense “People,” with a touch of humor in how the sampled vocals repeatedly exclaim “The fruitman!” with such enthusiasm. On “Bye.,” the gentle blips of the instrumental soften the clipped crooning that calls out “I … feel you” and “I wanna” — signs of tender attachment to the past while the beat, like life, marches on.

Filled with emotional and sonic texture, “Donuts” is sealed in a complete package by Dilla’s creative presentation. The 31 songs symbolize his age at the time of recording, making the album an extension of himself. Dilla also chose to label the intro as “Donuts (Outro),” while the outro is titled “Welcome To The Show.” The latter transitions seamlessly into the former; Dilla had connected the two ends of the album together. Not only did this choice shape the tracklist into a self-referential donut, but he refused to let his musical legacy run out of playtime.

Dilla’s influence on hip-hop production is indubitable, with his production equipment even being featured in the Smithsonian. However, the emotional potency and nonconformity highlighted in “Donuts” has made artists new and old fall in love with Dilla, whether it be Jon Bellion, The 1975, West or the Red Hot Chilli Peppers. Unlike many other aestheticized beat projects, it’s impossible to listen to “Donuts” as just background music. The album’s magic lies in keeping old memories alive — imbuing obscure samples with new energy, “Donuts” is Dilla’s fighting breaths as he channeled unbounded creativity into a memorial for the impermanent beauties of life.