The chorus of “Venus” lined up in the back of the Performing Arts Theatre Friday evening, dressed casually yet aristocratically while flaunting magnificent white judge’s wigs. “HOLD MY WIG” they seemed to say as one by one they tossed their wigs to a fellow judge and stalked forward to preach their opinion of the Venus Hottentot center stage. The Venus was almost naked, clad in beads, tassels and one sheer piece of cloth that failed to hide her enormous derrière. “An outrage!” the chorus cried — “It’s an outrage!”

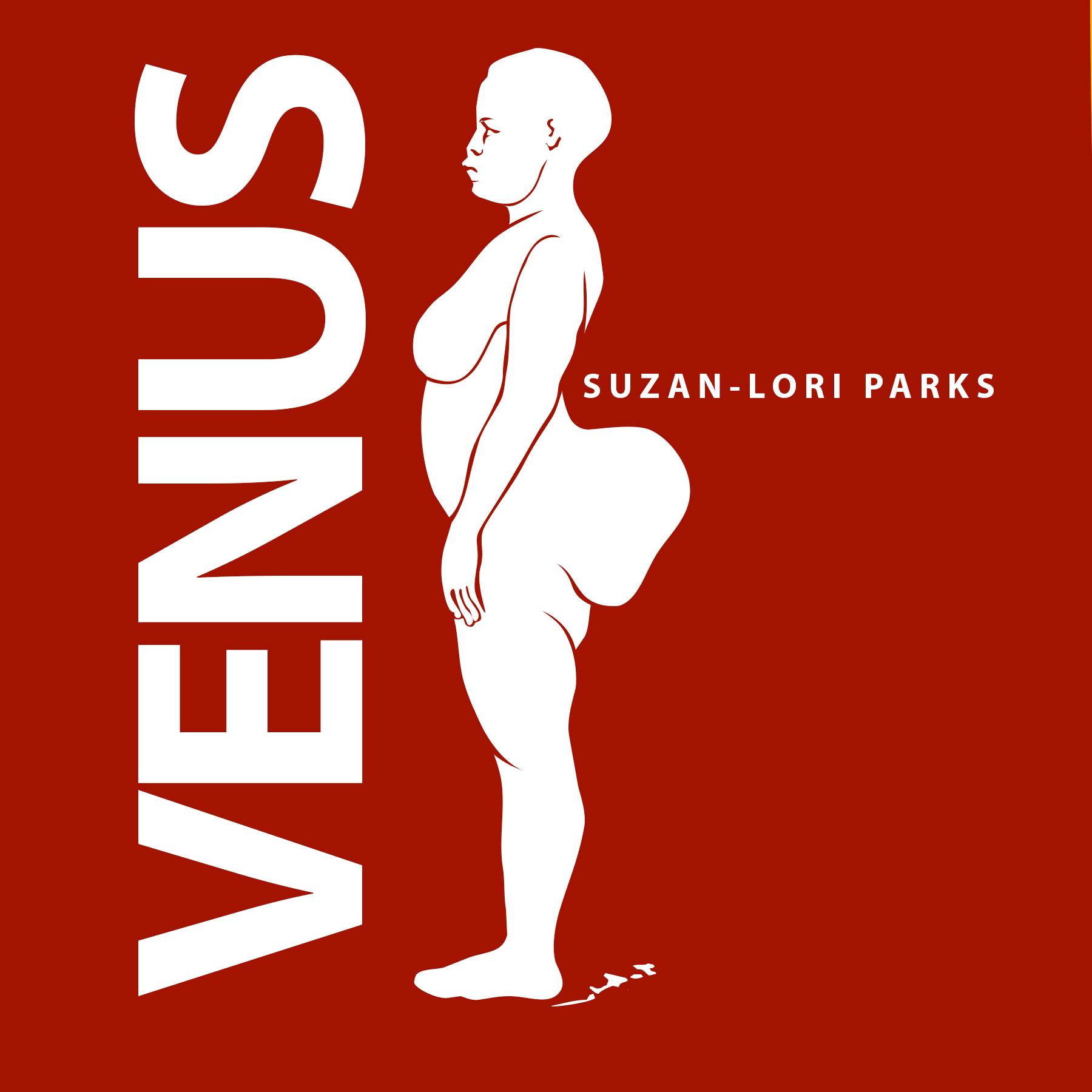

“Venus” is the creation of Pulitzer Prize winner Suzan-Lori Parks, and is based on the life of Saartjie Baartman, nicknamed Sarah. The Venus Hottentot was the main attraction of a freak show in London in the early 19th Century. Bachelor of Fine Arts program actress Tonea Lolin is a fourth-year, and was cast to play the Venus Hottentot. She wore a costume that mimicked the color of her skin and artificially enhanced her bum and breast areas to recreate the physical wonder of the “African Queen” — the Hottentot.

“This play is about time, distance and love, and the complexities associated with each,” Lolin described. “Venus herself is the essence of love, and the story shows how love is tainted when it is mistreated. Over time, this young woman, who had so many dreams for herself, was beaten down by the society she lived in and she never really had a choice.”

From freak show to medical specimen, Venus’s journey encompasses the intense struggles of being a woman of color and being different. “I love this play so much,” Lolin professed, “I hope that people now know what an amazing and brave woman Sarah Baartman was, and how her story lives on today.”

“Venus’s” director Tom Whitaker describes the play as “theatrical, powerful, poetic, challenging, funny, frightening and ultimately deeply human.” Given the blatant dehumanization of the Venus Hottentot as the main plot point, this final characteristic seemed contradictory. When asked for clarification, Whitaker replied that “Venus” brings to mind a line from the play “The Elephant Man:” “I am not an animal! I am a human being!” Whitaker feels that “Venus” challenges the audience to find their humanity, to be uncomfortable with the dehumanization of the Venus and to remember to treat their own fellows respectfully.

A particularly fascinating aspect of “Venus” is the play within the play. Here, the play within is modeled after a real French farce according to Whitaker, called “For the Love of the Venus, or the Hatred of French Women.” “It echoes the theme of fascination with Venus,” Whitaker said. “I don’t know that there’s any absolute one literal way to make sense of the play within the play … It is the almost absurdly picture-book version [of ‘Venus’] … In a certain way it tells the truth about [‘Venus’].”

Whitaker postulates that the play within the play is a necessary metaphorical element required to tell the story. “If you consider something like a good poem, there’s no way you can just write that poem in plain English — it has to be in the heightened language with the imagery that it has. It can’t just be said in prose. It’s the same with this play. There’s things that just can’t be said quite in literal language — the whole play is a poem in a way.”